Executive Summary

The internet is the defining technology of our age. Connectivity and information are utilities, like electricity or water, that touch and influence every aspect of modern life in ways we can and cannot see.

The fact that it’s happening does not necessarily mean we are happy about it. Internet-connected products and services are almost ubiquitous: often we use them without thinking; frequently we have no choice.

This new research from Doteveryone looks beyond internet usage and explores how the British public thinks and feels about the internet technologies shaping our world and changing our lives. It is based on a nationally representative survey of 2,000 people online and 500 by phone, backed by in-depth conversations in focus groups, which are quoted in this report.

This is the first of two reports on that research. In the second report we will present detailed analysis of the public’s understanding of digital technologies.

This report highlights:

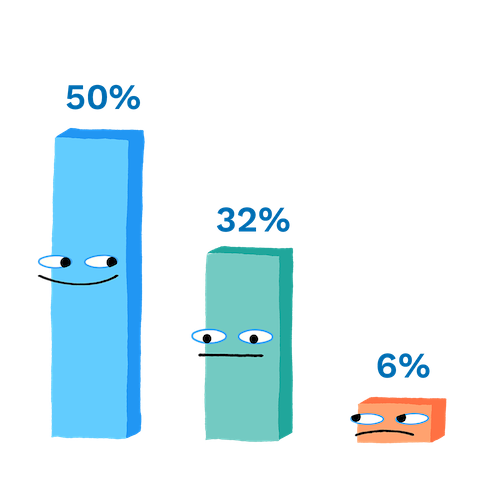

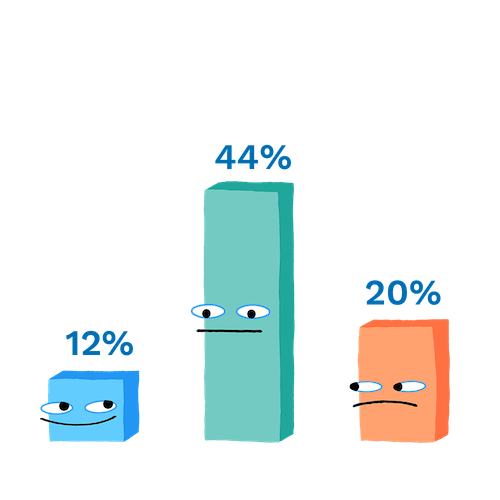

- The internet has had a strongly positive impact on our lives as individuals, but people are less convinced it has been beneficial for society as a whole. 50% say it has made life a lot better for people like themselves, only 12% say it’s had a very positive impact on society.

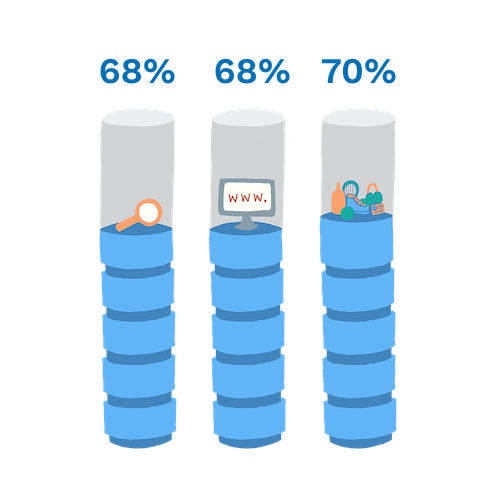

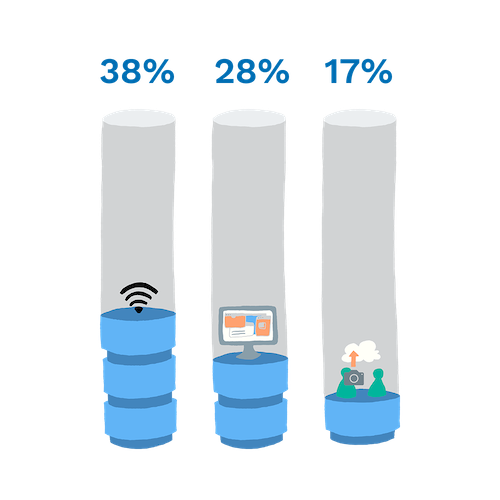

- There is a major understanding gap around technologies. Only a third of people are aware that data they have not actively chosen to share has been collected. A quarter have no idea how internet companies make their money.

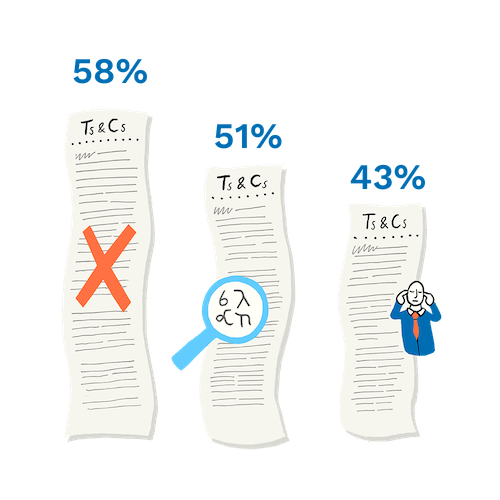

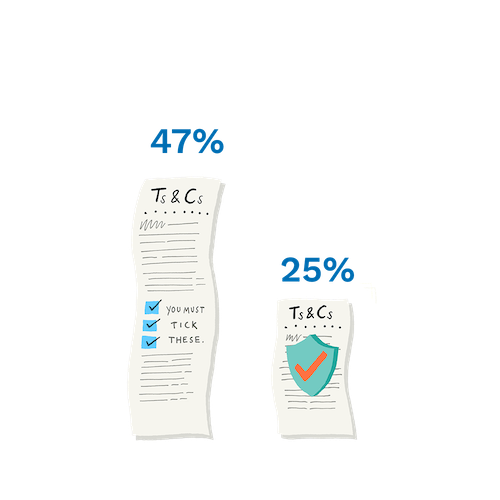

- People feel disempowered by a lack of transparency in how online products and services operate. 89% want clearer terms and conditions, half would like to know how their data is used but can’t find out.

- There is a public demand for greater accountability from technology companies. Two thirds say government should be helping ensure companies treat their customers, staff and society fairly.

Recommendations

Britain needs new ways to understand and respond to the social consequences of technology. We are not just 65 million people on our own digital journeys, but one society, being changed irrevocably.

This research shows a clear public demand for technology to be more responsible and accountable. Individuals are overwhelmed by the power and potential of the changes new technologies bring. These changes will get faster, rather than slower.

We must respond to them together, as a society, and create new ways to understand the impact of technology, new protections, and new accountability. This response must listen to public concerns, communicate clearly to the public about these changes and put public representation at its heart.

Based on the findings of this first national digital attitudes survey, Doteveryone recommends:

- Investment in new forms of public engagement and education, from both government and technology businesses

- Shared standards for understandability and transparency so everyone can understand more about the products and services they use.

- Independent regulation and accountability, so standards are upheld and people know who to turn to when things go wrong

1. Investment in new forms of public engagement and education

People love the internet—but not at any cost. When asked to make choices between innovation and changes to their communities and public services, people found those trade-offs unacceptable. This research shows the need for:

- The creation and maintenance of a rigorous evidence base about public understanding and attitudes toward technologies.

- Increased public digital understanding for everyone—not just children—and identifying potential harms to individuals and to society.

- Training public leaders in digital understanding—making sure those at the top of public services and institutions are able to take advantage of technology for the benefit of everyone and mitigate possible harms and unintended consequences.

2. Shared standards for understandability and transparency

People are fed up with online products and services which many feel are deliberately designed to obfuscate. 89% of people want clearer terms and conditions; more than half would like to know about the use and security of their data but can’t find this out. Our future digital society cannot operate if no one understands what they have signed up to. Technology companies should collaborate on and adopt:

- Clear, plain English terms and conditions that make it explicit how services operate and how personal information is used.

- Transparent, trustworthy design patterns that show how services work and decisions are made.

- Accessible ways for people to report concerns.

3. Independent regulation and accountability

People are not sure who they should turn to when they have concerns and are sceptical about how committed technology companies are to taking action when things go wrong.

This research shows there is public demand for:

- A single place for the public to turn to. Many different government departments or regulators already cover different aspects of technology—that’s partly why it’s hard for the public to understand who’s in charge. This body can direct the public towards the help they need and make sure that they get real accountability.

- Maintenance and upholding of standards and best practice.

- Incentivising responsible innovation that is good for society, not just good for business.