What if tech conferences don’t matter that much?

People who work in technology love conferences.

I don’t have a load of sentiment analysis to back that up — just 20 years of lived experience, and a Twitter feed full of conference conversations — but it feels like there’s a fairly constant need to:

- gather together with likeminded people

- show off about things we’ve done

- worry about the things we’re getting wrong

- complain about events while continuing to organise and attend them

Some of this is because lots of our work is abstract and intangible, so “meatspace” becomes more important and real. Some of it is because we’re a tribe of curious people who want to constantly learn and reflect. And some of it’s just because it’s lonely sitting at your computer all the time.

But two things are certain:

- Not everyone likes giving talks.

- Not everyone is asked to give talks.

And this creates a particular power dynamic:

- people who give good talks are seen as powerful

- people who are seen as powerful get asked to do more talks

- some people who haven’t done talks can’t imagine ever doing them

- some people who programme events only ask people they know are accomplished speakers

Which means that People Who Don’t Do Talks don’t do them and People Who Do Talks do more. (Doteveryone’s contribution to improving this is our fairer events fund: we want to remind conference organisers to design events in fair and inclusive ways, and get past the mindset of bolting on a token diverse speaker at the end.)

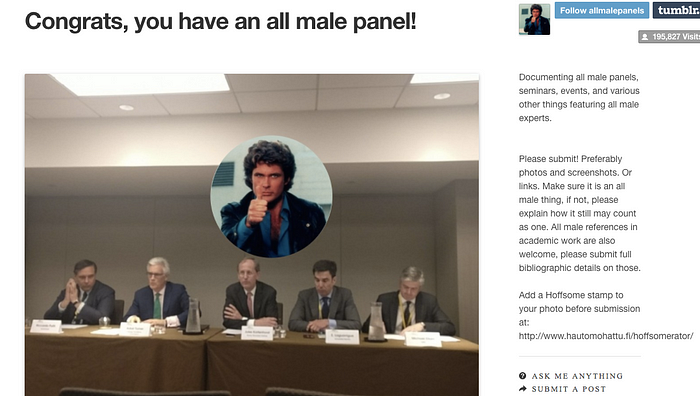

One reason conferences are important is because they’re a physical manifestation of who’s in charge, what is important, and who can have opinions.

But we should remember that just changing the people who are standing on stage is just changing the people who are standing on stage.

It’s not changing the management structures of organisations, it’s not redistributing power. It’s a sticking plaster.

Getting more women, more people of colour, more trans people and more disabled people presenting at conferences is important, but it’s an interim step. It’s accepting that powerful people are the ones that stand on stages. We should definitely make conferences better, but that’s just point 1 of what should be a 10 point plan.

If you work in technology and care about diversity and inclusion, then as well as all the things you know about — hiring inclusively, addressing your cognitive bias, not encouraging people to have sex at work, and organising better conferences — you should also think about making and nurturing power structures that don’t privilege being fearless in front of an audience.

It’s possible that more diverse and inclusive conferences will lead to different ideas circulating, different kinds of people feeling powerful, and different kinds of people being empowered because they see people like them on stage. But as someone who’s often called-on to be a last-minute token woman, I’m not sure my last-minute token presence makes that much change.

Because making conferences more diverse and inclusive is not going to solve diversity in tech. Conferences will only, truly, be more diverse if tech sector is more diverse.

Mary Beard wrote a terrific piece recently in the LRB that posed some good questions about about the interplay of power and prestige.

You can’t easily fit women into a structure that is already coded as male; you have to change the structure. That means thinking about power differently. It means decoupling it from public prestige. It means thinking collaboratively, about the power of followers not just of leaders. It means above all thinking about power as an attribute or even a verb (‘to power’), not as a possession: what I have in mind is the ability to be effective, to make a difference in the world, and the right to be taken seriously, together as much as individually. (my bold)

I keep coming back to this extract — it’s an important pointer for our work at Doteveryone for all sorts of reasons. I like it particularly because it sets out a positive vision of difference. Being an effective person who makes a difference in the world is not always the same as being a hero in a head mic.

After 10 years of giving talks, I’ve recently started to enjoy it. I like the discipline of organising my thoughts and telling a story. But I also have a stutter, so standing up and speaking in front of others is always quite fraught — I am, to be honest, always amazed that anyone asks me to do it. And, looking back, I realise I started public speaking out of frustration: I wanted a voice. And specifically I wanted a voice because I could hear others speaking but few of them were speaking to me.

But it’s taken me 10 years of practice to know how to structure a talk, do decent slides, and not fall to pieces when the words won’t come out of my mouth. I’m a competitive and impatient person; I couldn’t wait till there was a different kind of power structure I could participate in, so I had to take part in the ones I could see.

But we can’t just hear from competitive and impatient people.

We should also hear from people who are quiet, wise, compassionate, and nurturing. People who care more about good mental health than crispy pizza bases; who put work-life balance before working out. And the way to do that is not as simple as putting them on stage, or emphasising their otherness. It’s about creating structures that acknowledge different kinds of value. Hannah Arendt said that “power needs no justification … what it does need is legitimacy.”

And so we should start legitimising different voices and remember that credibility can come in different shapes and sizes. We can nurture that legitimacy every day in the work place through simple things like letting others speak in meetings, acknowledging their ideas and the value of their contribution. After all, not every role model has done a TED talk.

And in theory it should be easy for us to lift each other up, to divorce power from prestige: the technology industry is the most naturally networked in the world. The big platform businesses (Google, Amazon, Facebook to name the obvious ones) have achieved scale by making infinite connections: they are many-to-many, elastic not authoritative.

But it doesn’t quite work like that because those platforms aren’t co-ops or mutuals. They’re commercial start-ups that have scaled quickly, so the value we make by publishing content, selling products and chatting to our friends is not making a society: it’s making the data that makes the capital.

But seeing that we do know about networks, if we tried, we could do better.

Personally, I don’t think the technology sector will be truly inclusive until the futures and visions we’re projecting and the products and services we make are more diverse. (This is writ large in this description of life in the Tesla factory — that’s another blog post.) That doesn’t mean there aren’t some useful things to do right now.

If better conferences are step 1 of a 10-point plan, I have some ideas for steps 2 and 3:

Step 2. Listen more, speak less.

If you often have a platform in your place of work, use it as a way to consciously involve others. Make sure important decisions aren’t made in meetings where people are afraid to speak up. Call on other voices and seek alternative opinions. (I have to work really hard on this.)

Step 3. Acknowledge different priorities.

Although they might seem like the hardest possible problems, not everyone wants to launch a rocket or achieve the singularity. Just because we can do those things, it doesn’t mean they’re all that useful. I recently heard some design tutors discourage a group of young women from exploring the implications of domestic technology. They were encouraged to do something “bigger” and “more important”, but weren’t asked to explore how using technology in the home could help reduce the £2.5bn UK health and social care deficit. Different and domestic problems deserve a platform too.

These are indirect ways of making the workplace more inclusive and interesting for more people. There are loads more (add yours in the comments). Behaving more like this more often will help to make the tech sector more diverse, more challenging and, I think, more interesting.

So yes, let’s programme and celebrate better conferences. But let’s also not get distracted from what we’re really trying to do here. Conferences are a symptom of the industry; let’s make some change that really matters.