Dispatches from the Real World 03: Quakers in Britain

This is the third issue of Dispatches from the Real World. For more about this new series from Doteveryone, read our introductory post.

When’s the last time you were still? Not on your phone, not on a train, just…still?

Doteveryone’s Irit Pollak recently visited the Quakers, a religious group founded in England in the mid-17th century. For hundreds of years, they’ve been worshipping together in silence: no priests, no hymns, no sermons. But just because they’re quiet doesn’t mean they’re meek.

Can tech help a quiet faith find a bigger voice? And in a world of constant connection, could the rest of us use a little peace?

Friends, meet together and know one another in that which is eternal.

George Fox, founder of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers)

400 years ago in the north of England, a group of sixty Christians — farmers, weavers, and women — were busy becoming heretics. You didn’t need much, they said, to find God: no sacraments, no Gothic apses. All you needed was a group of people, sat in silence, ready to find the Light within.

Those were the first Quakers, and from them a movement grew. They were persecuted. They were executed. They were indulged. They found liberal causes: pacifism, abolition, prison reform. They founded businesses: Cadbury, Barclays, Clarks. Today there are nearly 400,000 Quakers around the world.

But that world is different than the Quaker founders’, and maintaining a religion takes more than quietude and inner light. So their faith is facing a new challenge: balancing human connection with digital connectivity.

Something has happened in the stillness that makes the heart more tender, more sensitive, more shocked by evil.

Rufus Jones, 20th century American Quaker

In the back streets of Hertford stands the world’s oldest purpose-built Quaker Meeting House. It still looks much the same as it did in 1670: twin red-brick gables, heavy plank doors. Every Sunday at 10.30 a.m., a handful of locals — mostly in their forties or older — quietly wait for God.

Teresa Parker is one of them. With her greying hair and mud boots, Teresa looks like someone who might run a bookshop or raise horses. She isn’t. Teresa’s trying to overthrow the prison system. She’s documenting human rights abuses in the West Bank. She’s a radical in a fleece gilet.

Raised Anglican, Teresa wandered into a Quaker meeting in 2003. “I was very tired of the way traditional church carries on,” she says. Drawn to the Quakers’ faith in action (“Quakers have this very strong connection between what they believe and what they do”) and a ready-made community, she never left; today she co-manages the church in Britain’s work in the Middle East.

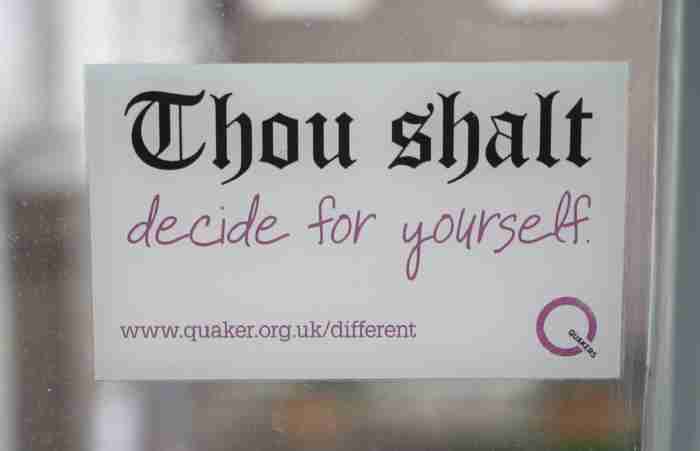

“I think perhaps we’re trying to be more strategic,” Teresa says — her team’s just hired someone to manage the programme’s presence online — “but it’s very difficult to speak for Quakers, because none of us speak for each other. The very nature of our belief is that we each have our own internal experience.”

As co-manager of the Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI), Teresa organises volunteers from 16 churches and NGOs to support and live alongside people in vulnerable West Bank communities. The stories are harrowing — miscarriages, poisoned crops, children frightened by gunfire.

“Our work is a combination of presence on the ground and advocacy to the wider world,” she says. “And obviously digital media is such a growing area.” So GoPros are going to the field, and the volunteer application now asks for video editing skills alongside Hebrew and Arabic. Over the past year, volunteers have published more than 50 blog entries about life in the occupied territories. They remain largely anonymous (just a first name, no photos); this helps keep volunteers safe, although not social-media-optimised.

But beyond the stories, EAPPI’s volunteers — and Teresa herself — are nearly invisible. (Her name isn’t even spelled right on the programme’s website.) It’s not in Quakers’ nature to make much of themselves, but it is easier to make change when people know you’re doing it. For Quakers, finding that balance between humility and self-promotion is an ongoing struggle.

Social media tends towards the shallow and boastful. That’s not an intuitive fit for the meticulous work of ecumenical accompaniment, nor for a faith that values authenticity and depth. However, Teresa and her team know they need to do more — not despite their beliefs, but because of them. After all, faith without works is dead.

Although the programme’s growing high-tech, its roots remain as traditional as ever. “I get my energy, and my strength, to do the work I do by going to Quaker meeting,” Teresa says. She comes back to the old meeting house every Sunday to disconnect from the world, to revel in the quietness. “Sometimes you can almost feel like you’re being held by the silence of others.”

Keep in the light, which is one, in the power, which is one, in the measure of life made manifest in you, which is one. And here is no division, nor separation, but a gathering and a knitting.

Margaret Fell, “mother of Quakerism”

Of the 400,000 living Quakers, nearly half are in Africa and the rest are everywhere else. Jane Dawson is head of external communications for the Quakers in Britain; in addition to sharing their work with the world, she’s figuring out how to connect Quakers with other Quakers.

“We’ve got 25,000 worshippers in the UK,” Jane says. “In Kenya, we’ve got 100,000. One of the things we’re beginning to really think about is how the world network of Quakers can begin to associate with each other.” Back in the 1600s a single letter could take months; today there are Facebook groups, online courses, even virtual meetings for worship via Skype.

Like Teresa, Jane’s looks are deceiving. Her sensible heels and soft cardigans make sense in London, but it’s harder to imagine them in the mountains of Rwanda. That was a few years ago; she’s just back from her most recent trip, the Quaker Yearly Meeting in South Africa.

“The issues that Southern African Friends have to face are very different,” Jane says. “But the values enable people to have the strength and the faith to challenge things in really difficult situations. Our main tenets of peace, justice, sustainability, and equality, they’re still important.”

Just as in tech, decentralisation — building a more networked approach — is high on Quakers’ agenda. But that journey is perhaps easier for a faith fundamentally opposed to hierarchy. Now, rather than try to hang onto old models, Quakers in Britain are actively (and continuously) checking their power and privilege.

“I don’t think we’re the mothership any longer,” says Jane. “African Friends are doing amazing work. We’ve got to learn from them. All we can do is provide information on how we’ve done things in the past — and if that’s useful and valuable, brilliant.”

Much of that information is about process. While worship styles may vary, Quakers feel strongly about governance. There are hundreds of books stored in London’s Friends House and thousands of records stored on quaker.org.uk. There is a shared agreement about how to meet, how to speak, how to stay silent. “One of the things that has enabled the Quakers to survive is that we have discipline,” says Jane.

As core as tech is to her experience of Quakerism, Jane — like Teresa — still finds the most satisfaction from quiet, collective ways of worship. “I also meditate, do a lot of yoga,” she says. “I know what it feels like on my own. But doing that in community, with other people, it’s a different level. That’s when something fundamentally shifts.”

Avoid hurtful criticism and provocative language. Do not allow the strength of your convictions to betray you into making statements or allegations that are unfair or untrue. Think it possible that you may be mistaken.

Quaker Faith and Practice, 1.02

Quakers are adapting to meet the demands of a digital world. But many of their ways of thinking and working — rooted in understanding, community, intuition — could serve as models for a tech sector where personality and productivity often take centre stage.

Tech is fundamentally about innovation, and that innovation has extended beyond products and services to overall ethos. Technologists have their own sacred texts: Facebook’s “move fast and break things”, Google’s “don’t be evil,” Apple’s “think different”. And while these approaches are profitable, they rarely account for the humanity of the people doing the work.

That isn’t to say tech doesn’t care about treating people well. From Google to Microsoft to Creative Commons, tech has made real and good efforts to identify codes of conduct and ways of operating that affirm and build trust. But rarely do they put so much onus on the individual (“you must” as opposed to a lighter-touch “we believe”), nor do they join up to the processes of working themselves.

Quakers may struggle to understand technology, but they understand people — and through hundreds of years, they’ve learned that understanding people requires gentle guidance and continuous work. That means clear processes, as clear as any style guide or pattern library, about how to treat one another. If you’re quiet, speak up bravely. If you’re loud, give others a chance. Don’t try and be clever. And above all, don’t assume what you want is what everyone else needs.

Quakers call this overall decision-making process “discernment”, and it’s different from top-down dictates or majority rule. Supported by clear processes and connected by a shared purpose, they ask God to guide them towards the right answer. And when they find the right answer, they write it down so everyone can see. (Those hundreds of books at Friends House? They’re largely “minutes”, well-structured references to all the decisions Quakers have ever made.)

When it comes to tech, billions of lines of code have been open-sourced. The same cannot be said of the decisions that led up to them. What might a Github for choices and insights look like? How much better would actors act if they knew others could see — and how much more would we trust if people could see the inner workings of why, not just how, technology works as it does?

Tech may not have a higher power on its side, but big businesses and social good startups alike tend to be organised around a common cause. Could the things that work for Quakers, the clear processes and citations, be a more humane (and better trusted) alternative to “move fast and break things”?

No moment of silence is a waste of time.

Rachel Needham, 20th century British Quaker

A few blocks from the Hertford train station sits the old brick building that’s held Quakers for 350 years. The meeting starts at 10.30 on Sundays; you can sit wherever you like, and every old pine bench is the same.

Let yourself relax. Your mind will go a million places: what am I doing? What have I forgotten to do? How has it only been ten minutes? Who are these people and why does their clock tick so loudly?

It will be tempting to blame your lack of focus, your spinning mind, on tech — on the endless stimulation of modern society. But the red-bound book of Quaker Faith and Practice is full of stories, hundreds of years’ worth about how hard it is to stay focused.

It turns out people, whether in 1718 or 2018, just aren’t good at sitting still. But, as American Quaker Douglas Steere said, “In this life we find the time for what we believe to be important”.