13 things to think about after attending an international conference on human rights in the…

13 things to think about after attending an international conference on human rights in the digital age — RightsCon 2018

Last month, I attended RightsCon 2018 in Toronto, a conference exploring human rights in the digital age. By the end of the three days, I’d heard new and repeated themes that raised more questions than they answered.

1. Is Facebook really to blame for everything? I don’t think I attended a session where Facebook wasn’t mentioned. Is it just an easy story or is there something deeper going on? Cambridge Analytica seemed merely an afterthought, or a way to underline the iniquity of Facebook. I got the sense that Facebook was a proxy for consumer-led big business. It didn’t matter how strongly the speakers actually felt about Facebook. Just mentioning it showed you were against corporate irresponsibility and erosion of privacy. I wonder who the fall guy will be next year?

2. Should codes of conduct be implemented in all spaces? Having the code of conduct in such a visible location (upright banner next to registration desk) forced me to see it, read it and take it in. I had never seen one visibly displayed and at first I wondered (fairly dismissively) whether this was a North American or human rights thing. However, my mind kept coming back to it and the fact that I thought it was strange to see a set of values displayed. Why was that? Did I assume they don’t need stating as it was surely just good behavior and any attendees should already understand how to behave? But this code was about more than not being awful and excluding those who stepped out of line, it was about including everyone and making them feel welcome. Imagine seeing that on public transport, in public spaces, at work?

We strive to treat people with dignity, decency, and respect, and to build a community for everyone, free of intimidation, discrimination, or hostility — regardless of gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, nationality, origin, race, ethnicity, religion, age, disability, or physical appearance. We do not tolerate harassment in any form.

RightsCon 2018 Code of Conduct

3. We need trained moderators and platform accountability. Platforms have full control over content and that includes whether or not it remains published. Many moderators are not trained, yet are making decisions on what does or doesn’t violate policy or even law. Many decisions are made using moral judgement, have no legal grounding and can often be wrong. Platforms are under heavy scrutiny, and not acting is seen as condoing an action/group/message so there is a pressure to remove anything that could offend. Platforms control our free speech without any real accountability. The point was made that no one sends a letter saying that you can’t speak in certain parts of the country because someone complained, and you can’t know why the letter was sent or by whom. So why do we accept this online?

“Platforms control our free speech without any real accountability.”

4. There is a power imbalance between those who design, sell and regulate technology and those who use it. Many technologies were designed for specific things by a specific group of people. In spite of this, other groups have used these tools to work for them. I have seen social media used as a platform for disparate voices, but these voices find access by breaking the system, so even though they are perceived as belonging, many of them feel that they are still working in an exclusionary system. When we make decisions such as stopping supporting software and devices because they’re old or less frequently used, we need to consider that although they may have a small minority of users, those users are more likely to have a low socio-economic status and/or a minority status as they take longer to upgrade.

5. Globalisation needs to account for local nuance. Technology seldom, if ever, has implications for only the region in and for which it was designed. Technology is global and consideration needs to be made for that, particularly where globalisation is a deliberate strategy and not a happy accident. English only is not acceptable on a global scale, but addressing language isn’t enough. When designing platforms and technology and moderating content, there needs to be an understanding of the effect of actions at a local level and this means finding some way to access a local perspective. Can community standards be valid globally when we live in different cultures and have different values and viewpoints?

6. The global south and global north have different views about who should have oversight of technologies. In the global north there is a distrust of large tech companies and there are calls for government regulation (e.g. GDPR) to rein in organisations and hold them accountable. However in the global south, many governments are seen as corrupt and citizens’ trust in them is low. Tech companies are seen as no worse than the government and technology as something that may work better than human corruption.

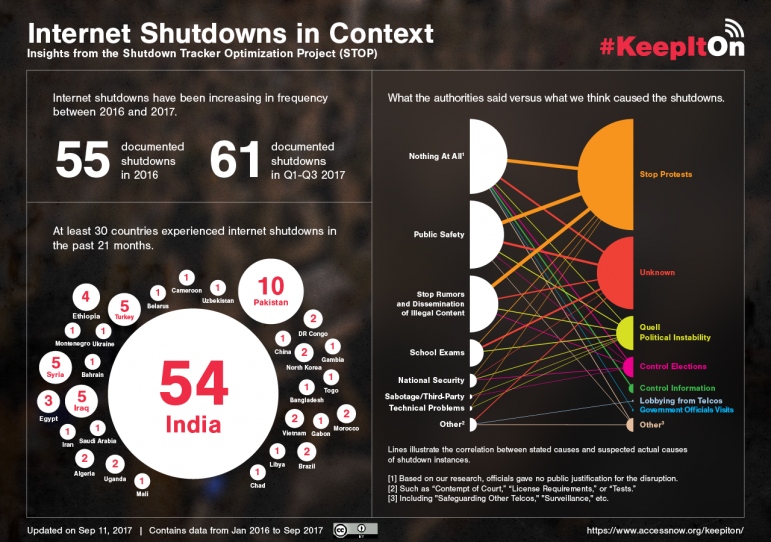

7. Can we escape surveillance anymore? What does it mean to be truly offline? As a speaker pointed out “we can choose not to buy Alexa but we can’t opt out of a public space.” Smart Cities are on the rise and often the public is completely unaware that they are being monitored and by how much. Even if they are aware, they may not have a choice. Somaliland became the first country to use iris recognition to vote and the EU has approved a new system that will store biometric data and entry/exit information of all visitors. Surveillance isn’t just about physical spaces and bodies, online it is rife and much of it is unnoticed. Many countries are censoring platforms and enforcing internet shutdowns. Access Now’s #KeepItOn campaign and the Ooni tool both highlighted their work in monitoring internet surveillance.

8. Does RightsCon think that China is no longer important? If you look across the schedule of over 450 sessions, only nine were about China (only two of which referenced China in the title). This was a very surprising omission to me as with the rise of the Social Credit System and the piloting of surveillance and monitoring technology in Xinjiang, China is embedding technology when other countries are still discussing the ethical and moral implications. Once we start ignoring this, we are sending the message that this is acceptable. As Vietnam deepens its partnership with China, we should be aware that the problem is spreading.

9. Algorithmic bias is a lot more complex than we think. There are different types of bias: statistical, moral, legal, social, psychological, etc., and quite often we use statistical bias (e.g. missing group of people) as a proxy for moral bias. In order to offset the bias that already exists in a system, we may need to bias the dataset relative to statistical distribution (e.g. remove data that skewed racist).

So when (if ever) is it okay to be biased?

Gawain Morrison from Sensum raised an example that struck a chord: take a hostile workplace and create an algorithm to recruit workers who will fit in. If minorities and women are ignored the algorithm can be said to have worked and not been biased. In this instance, the problem isn’t the algorithm, it’s the workplace. AI is raising questions about what constitutes a “good” society. Let’s address the underpinning systems and not just use data and algorithms as a bandage.

10. The right to travel doesn’t exist for many. RightsCon moved location to Toronto from San Francisco in protest against Trump’s travel ban; however, many sessions still began with a notice that a speaker had been unable to get a visa. Speaking to attendees from India, China, Nigeria among other countries about their struggles to attend as well as previous holidays and conferences where they were denied visas or even the right to leave their own countries really brought home to me the privilege of my UK passport in a way I hadn’t confronted before. We rail against Brexit as it will make it harder for us to travel, but our worries are about the increased time and cost (both perfectly valid). We don’t have to worry about whether we’ll physically be allowed to travel.

11. Is Facebook better than no internet at all? I found it fascinating that when half of the world is pointing the finger at the evil’s of Facebook, there are many countries that wouldn’t have any access to the internet without Facebook. In countries such as Nigeria and Indonesia many people believe that Facebook is the internet. Infrastructure and cost mean that many people do not own or cannot access computers and mobile apps are their only option. Facebook (including WhatsApp) has built a sizeable market. Without them, there would be no online access for many.

12. If it doesn’t exist online does it exist at all? The session that stayed with me the longest was a mapathon where we mapped a Palestinian village to have documented proof of its location and infrastructure to prevent it being torn down. There was a political back story here, but that didn’t disguise the fact that increasingly, we see online as the default state. As automation becomes more prevalent, what happens to those people and things that don’t exist online? Will they be forgotten or dismissed?

13. How useful is a conference if everyone is saying the same thing? Innovation is all around us, just not in the structure of conferences. We continue to be talked at by a bunch of experts with a few questions shoehorned in at the end. Many of the sessions at RightsCon had overlapping content; the examples may have been slightly different, but there were only so many times I could hear about the need for regulation and how automated bias should be stopped before I started wondering why I had to hear it more than once?

“I’d like to leave with some solutions not just more questions.”

Conferences seem designed to make me fill up my notebook and take photos of pretty slides, but I rarely get the opportunity to explore ideas either in discussion or practically. I’d like to leave with some solutions not just more questions. Instead of 10 talks about a theme, what about one or two talks, a few roundtables and then a few workshops with the remit to produce? Let’s mix it up.

Final thoughts

There is a prevailing narrative that big tech companies are the enemy and need to be stopped or monitored. I agree that the real effects of technology mean that checks and balances are needed but I am not sure that the current landscape is a healthy one. At the end of the day we’re all part of the same society and dividing it into “us” and “them” just fosters the same exclusion that conferences like RightsCon are supposed to stand against. Why didn’t we hear from the big tech companies?

Intersectionality and multi discipline are more important than ever. RightsCon shows what happens when people from all different areas come together to address concerns and this is what is needed within organisations. Instead of working in single discipline silos, we need to consider other perspectives right from ideation. To paraphrase Jamilah Lemieux’s powerful speech about including Black women:

We have to build that table with you in order for that table to be stable. Don’t invite us to the table after it’s set.

13 things to think about after attending an international conference on human rights in the… was originally published in Doteveryone on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.