It’s time for tech to prioritise responsibility over ratios.

It’s time for tech to prioritise responsibility over ratios.

Matt Stempeck, researcher at Civic Hall and Corporate Overlord at the Bad Idea Factory

In support of our work championing responsible technology, we’re inviting leading practitioners, thinkers and funders from around the globe, who are exploring the impact of the internet on people and society, to share their insights and experience.

For this initial series, we asked contributors to give their view on how the field of responsibility technology is changing. Each author addresses different questions which may relate to the history of the movement, why it is important, where it may be going and what’s needed to bring more of the thinking into practice.

In this piece, Matt Stempeck , researcher at Civic Hall and Corporate Overlord at the Bad Idea Factory discusses why the tech industry needs to start taking responsibility for the negative things that can happen when we build, fund, or use tech and asks whether civic tech has the answers.

For years, the tech industry has celebrated a couple of key metrics that demonstrate the success of their software platforms: users per employee and revenue per employee. To investors, these metrics indicate an efficiently leveraged company. To engineers, the ratios are proof of technical efficiency.

In one of the most famous examples, Instagram had 2.3 million users per employee when it was acquired by Facebook in 2012.So the more lopsided the ratios, the more investment-worthy the platform is deemed to be.

But unbalanced employee-to-user ratios may also be telling us something else — evidence of irresponsible tech.

Let’s consider the example of Facebook in Myanmar. People have used Facebook in Myanmar to incite violence for years. And for years, Facebook has been recklessly slow to respond to this terrible manipulation of their platform According to Facebook’s Erin Saltman speaking at Re:publica, Berlin in May, the company simply didn’t have employees on their Operations team who understood the local context of what was happening in Myanmar, despite the formal briefings NGOs had offered Facebook’s policy team over the years:

“We need hyperlocalized understanding. We need very good language understanding on the ground…We needed a more robust infrastructure there. We needed operations teams that really had an in-depth understanding, so those teams have grown substantially.”

In Wired, Timothy McLaughlin further unpacks how Facebook prioritized growth while abandoning responsibility in Myanmar:

“A slow response time to posts violating Facebook’s standards, a barebones staff without the capacity to handle hate speech or understand Myanmar’s cultural nuances, an over-reliance on a small collection of local civil society groups to alert the company to possibly dangerous posts spreading on the platform. All of these reflect a decidedly ad-hoc approach for a multi-billion-dollar tech giant that controls so much of popular discourse in the country and across the world.”

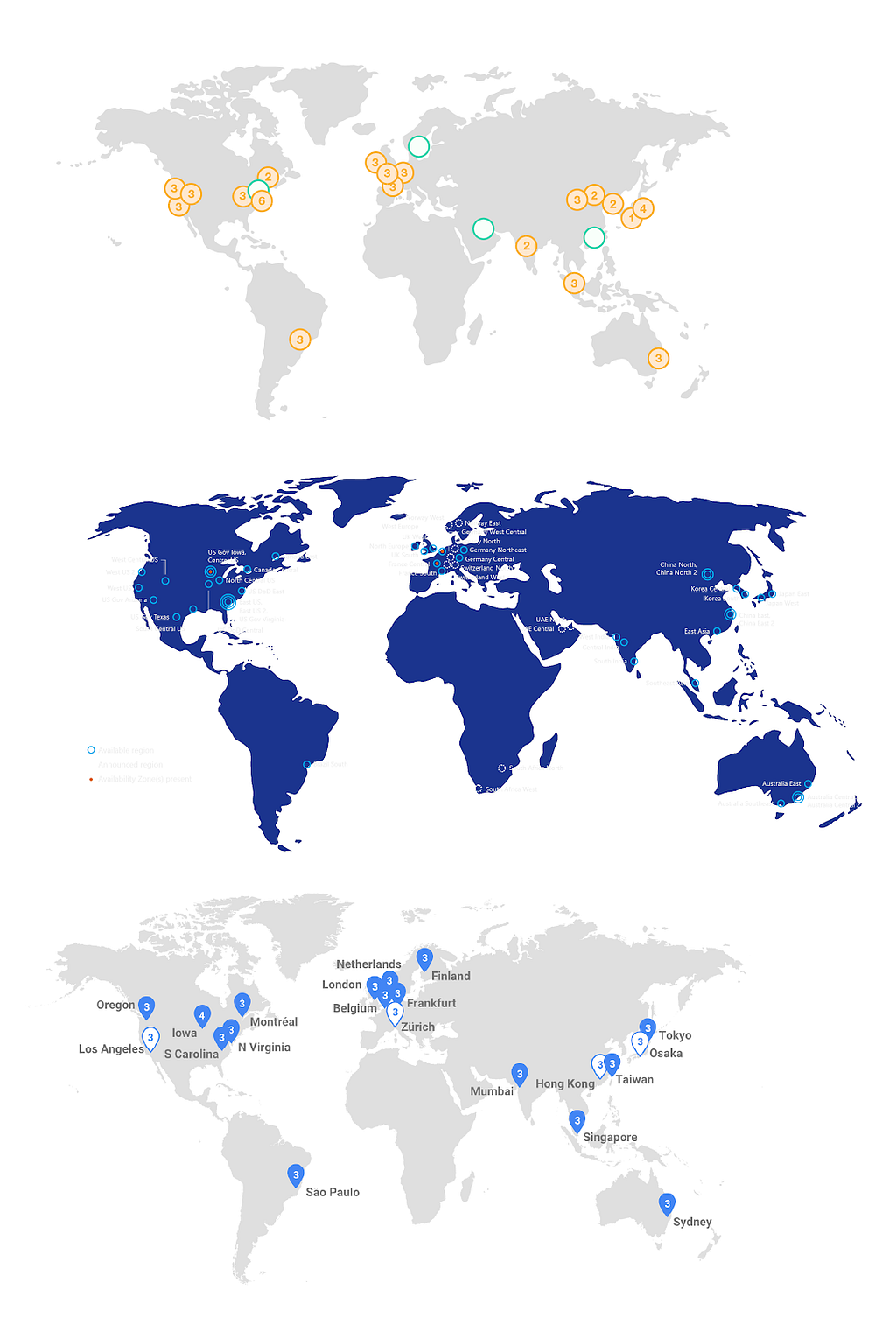

To their credit, Facebook has now hired up a team with that critical local awareness in Myanmar. Saltman goes on to say that Facebook’s local operations teams are growing, not just in California, but in Facebook offices around the world. But without transparency from Facebook or other tech companies, we can’t know for sure if they have adequate human resources with cultural and political literacy wherever they have users. So far, that’s a commitment we can expect only after a social media platform has been used to incite fatal violence. At the very least, it’s no longer a good look to highlight how few employees you’ve hired to support and protect billions of users.

Scaling without considering the consequences

Technically, it’s now easy to make your software scale the globe. Spin up some additional zones on your cloud provider of choice, translate the user interface, and boom, you’re in a new market. But socially, global scale isn’t so simple. The arrogance in thinking that it can, that a subcontractor dealing with a torrent of grotesque speech and imagery at work every day will know how to respond to a complex foreign affairs issue communicated in coded language in southeast Asia, is the definition of irresponsible.

Media and information ecosystems vary dramatically around the world, as do the regulatory approaches different nation states take to press and technology. The ways different groups of people use identical technologies can be far more complicated than tech companies’ “localization and “internationalization” teams have respected. Look only as far as false Whatsapp rumors leading to mob killings this year and last. People around the world are paying the price for the “move fast and break things” approach to product roll-out.

Tech companies have been able to build wildly successful products that tap directly into the human brain’s pleasure and anxiety centers, enabling the products to basically grow autonomously. As an investor, what’s not to like?

But in too many contexts, the social media platforms we once celebrated are making the fights for democracy and human rights and peace more difficult than they already were. It’s like working in quicksand. The people building social media platforms had not considered, could not know (nor were they exactly rushing to find out), what it would mean to launch the largest-scale social intervention in human history with essentially no one monitoring the results. What happens to media ecosystems when the platforms everyone uses daily consistently reward the most emotionally resonant content with amplification? What might occur if tech companies roll out global messaging services that allow groups to swiftly forward an endless stream of anonymous rich media messages at nation-state-scale?

It feels like the people in charge haven’t taken the growing number of issues seriously enough. They don’t trust their users to be part of the solution, and more than anything else, would rather not dedicate many resources to solving problems that interrupt the efficiency, and ultimate profitability, of their wünderproducts.

The building backlash against irresponsible tech

For years, content moderation experts have operated in silos, sitting within “Trust & Safety” departments, and asked to mitigate and smooth out the negative effects of social media on humans, yet without being given the power to address their root causes. Their concerns were never treated with the same weight inside the company as ‘growth hacking’ priorities, or founders’ whims.

While the backlash against irresponsible tech has catalyzed remarkably quickly (driven in part by its role in helping elect the least popular US President in decades) the pressure has been steadily building for some time. For years, even the most tech-literate among us have grown tired of playing cat and mouse with privacy settings. And that was before we knew how often companies were ignoring even our explicit opt-outs, or mining our text messages and call logs.

But the chorus of critics has grown louder and better funded, and data literacy and privacy have become more mainstream topics. And as a direct result, the aura of working for these companies is no longer what it once was. This matters to the companies. Their brand is an incredibly important factor when they’re recruiting or retaining top talent, because their competitors are already offering similarly great pay and benefits.

There are also many, many more technology ethics courses than there were even a few years ago (here are over 200). A college course does not an industry norm make, but this is an important trend that we should encourage so that awareness of ethical issues is no longer an excuse for irresponsible tech. I’m already jealous that many of today’s students may get to pre-emptively learn the lessons we had to go through.

More civil society groups are advocating for responsible tech, as well. In addition to Doteveryone, there’s new work coming out every day from Data & Society, Platform Cooperativism, The Center for Humane Technology, the AI Now Institute, MIT Media Lab’s Ethics of Autonomous Vehicles, books like Technically Wrong and Weapons of Math Destruction, and the $27 million (to start) Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Fund.

But still, there’s significant work to be done to ensure responsible tech advocates preach beyond the choir. For example, of Americans with a negative view of the internet’s impact on society, only 5% attributed that view to “privacy concerns or worries about sensitive personal information being available online” (Pew Research Center survey conducted in January, 2018) (see Doteveryone’s People, Power and Technology reports for similar research on the digital attitudes of the UK population).

Civic tech must be responsible tech

The field I’m most interested in, civic tech, has an even greater responsibility to build ethical tech. First of all, we claim social good as our mission. If we do harm, we are categorically failing in that mission.

Some startups begin life as civic tech projects, before making hard pivots toward profits. The Point, a site where people could go to take collective economic action to help form a tipping point together to drive concrete, positive change in the world, became Groupon, the global e-commerce marketplace with a reported revenue of 28.58 billion USD (2017). PolicyMic was a civic platform where young people were to escape their echo chambers and engage in informed, level-headed policy debates. Now Mic.com, the American internet and media company catering to millennials attracts over 40 million unique monthly visitors.

Dramatic growth is what matters most when you’ve borrowed Venture Capital money. Other priorities, even if they’re for social good, get jettisoned. Groupon’s main impact on the world ended up being less catalytic social movement, and more employing armies of sales people to harass small business owners into running promotions of questionable business value, all while sailing the unsustainable business towards a cash-out IPO. PolicyMic pivoted from civil policy discussions to exploiting the social justice passion of the very generation they originally sought to empower for traffic to Mic.com.

And civic tech is often “designed for”, as opposed to designed with”, the vulnerable populations many civic tech products are designed to help; users who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, and more likely to face deep racial, gender, and heteronormativity biases in their daily lives.

Many of us building civic tech hope to shift the power to the people and reform our democracies into more participatory and equitable systems. The idea that civic tech adopts any of Silicon Valley’s dark patterns in the hopes the ends will eventually justify the means should really be a non-starter.

Initially, the first generations of civic tech projects, which we track in the Civic Tech Field Guide, applied new tech to solving old problems. We could enhance civic engagement, for example, if a country’s legislation was easily available online to read and annotate.

But as we’ve opened our eyes to the downsides of technology, a new generation of groups have been forced to address the problems created or exacerbated by tech itself. Some algorithms which are responsible for making major decisions about your life, like which school your children attend, or whether you’re allowed out on bail, are trained on racist sample data, producing racist algorithms that extend and encode existing biases. The tech industry itself is overwhelmingly led by White or Asian men. This results in glaring oversights in the products meant to be used by the whole population. The digital platforms that organizers have adopted to build social movements have, in many cases, exposed those movements and those organizers to harassment, hacking, and surveillance. New groups and projects are springing up to take on these challenges, but they can’t possibly operate at the scale of billion-user tech companies.

Our best hope is challenging the tech industry to make responsible tech the new normal.

But this will be an enduring challenge

The backlash against irresponsible tech that’s emerging requires a broad, and deep shift in culture and practice.

We’re already seeing a few societal feedback loops coalesce on this topic this past year, that previously remained separate: public outrage, sustained media attention, and negative business results.

The media can inform public sentiment by covering data privacy stories they once ignored. It can seem like an eternity before professional news companies pay attention to your cause, but at least for the time being, the media has discovered that people care about irresponsible tech and is consistently covering it. This naming and shaming is a powerful force in society because mass media can change mass behavior. Then, investors’ expectations of consumer backlash can and do influence stock prices. So too does the specter of regulation.

The choices of powerful individuals and mass behavior shifts alike can drive meaningful progress toward making the responsible tech we want to see become the industry standard. We’re now outside the age of naïveté and innocence where technology companies can no longer say they didn’t know. They’re responsible for what they do next.

The tech industry must also internalise a responsible tech mindset and ensure that it remains an ongoing concern. We can’t “solve for” the misuse of tech by bad actors, because bad actors are humans and humans are especially good at adapting to game systems. We can’t engineer our way to the answer any more than we can engineer our way to world peace. Yet the engineering mindset continues to point us to the same old bag of tricks: user content flagging, 5-star ratings systems, and most recently, artificial intelligence. The current rush to develop systems that algorithmically identify and suppress disinformation as it moves around the internet, and even messaging services may look misguided when, say, five years from now, these same detect-and-delete systems are readily adopted by authoritarian governments to censor legitimate speech in private communications with ruthless efficiency. There’s no shortcut to figuring things out together in a democracy.

None of the tactics we have or will develop in the future are silver bullets. There will be no AI technology that will allow tech companies ignore their responsibility to pay close attention to how their products are being used by their billions of users.

If we’re going to trust our lives to autonomous vehicles, Internet of Things devices and drones the first thing we need to do is abolish from our minds the notion that protecting these systems from misuse is anything less than a perpetual, daily battle. And we can no longer say we didn’t see that coming.

It’s certainly a challenge to predict, track and quantify both the positive and negative impacts of the tech we create. Particularly technology that is rewarded by investors for demonstrating how they meet a very particular set of metrics which do not consider the intended consequences of the tech that they are developing has on society. Like what is the environmental impact of Apple launching its Maps application to hundreds of millions of iPhone users without including mass transit directions, because it saved the wealthiest company on Earth some money compared to licensing directions from Google?

Or what effect does it have on democracy when social media companies prioritize the artificial growth of bot accounts over their actual users, who must resort to closed groups to safely express their political opinions?

We don’t really know. We’ve never really known. But we do need to start taking responsibility for the negative things that can happen when we build, fund, or use tech.

Interested in contributing your thoughts and experiences working in the responsible tech field? Get in touch with us and let’s arrange a chat. [email protected].

If you enjoyed this, please click the ? button and share to help others find it! Feel free to leave a comment below.

Matt has been researching and building civic tech since 2005. He has done so across electoral and issue campaigns, national and city governments, academia, and journalism. In 2016, Matt led the Digital Mobilization team at Hillary for America, which included the campaign’s voter registration, peer organizing, and SMS technologies.

Matt most recently served as Director of Civic Technology at Microsoft, and is now building the Civic Tech Field Guide to better connect the world of civic tech projects. In his spare time, Matt works on projects that don’t really need to exist, with a collective known as the Bad Idea Factory.

Matt holds a Masters of Science from the MIT Media Lab’s Center for Civic Media and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Maryland’s Government Honors program.

It’s time for tech to prioritise responsibility over ratios. was originally published in Doteveryone on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.