Some lessons from building a digital public health campaign

Some lessons from building a digital public health campaign.

Let’s start with four but we know there’s more…

Earlier this summer, Doteveryone launched Be a Better Internetter — a digital public health campaign.

This was an experiment — we wanted to find out whether it’s possible to find simple and positive ways to show people how to make their tech work better for them. (It was also great fun: most think-tanks produce long and serious reports, we’ve made an animation with a dancing pair of sunglasses.)

We knew from our People, Power and Technology research into public attitudes and understanding that people don’t really get how their tech works. They also welcome practical tips to help them make it work better for them — 42% said they’d like to change their privacy settings, for example, but didn’t know how.

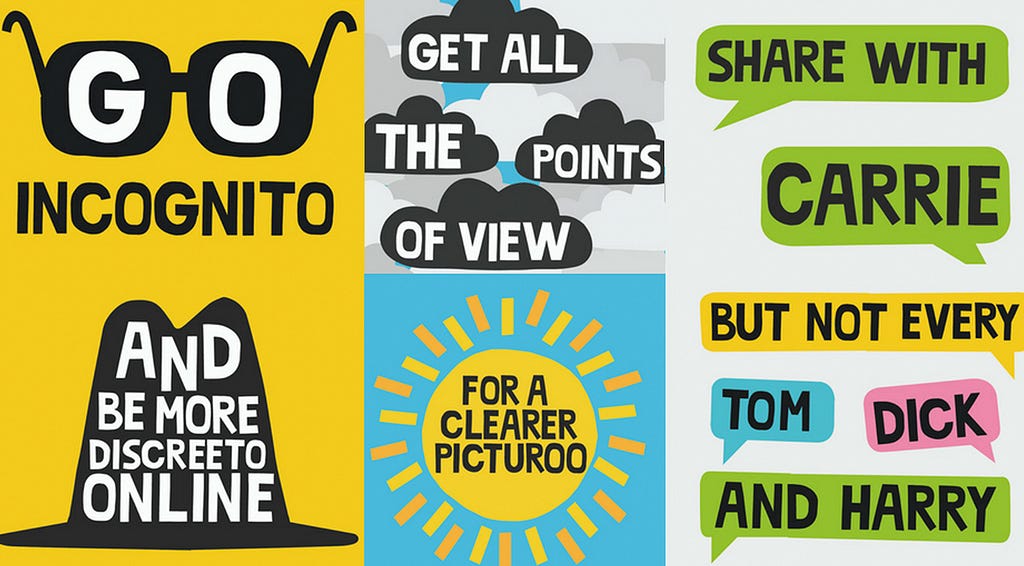

So with support from Omidyar Network, creative agency BETC and the Guardian, we launched a set of three adverts under the banner ‘Be a Better Internetter’ to see if we could meet that need.

Here’s (some of) what we’ve learned:

1. People want this kind of thing to exist

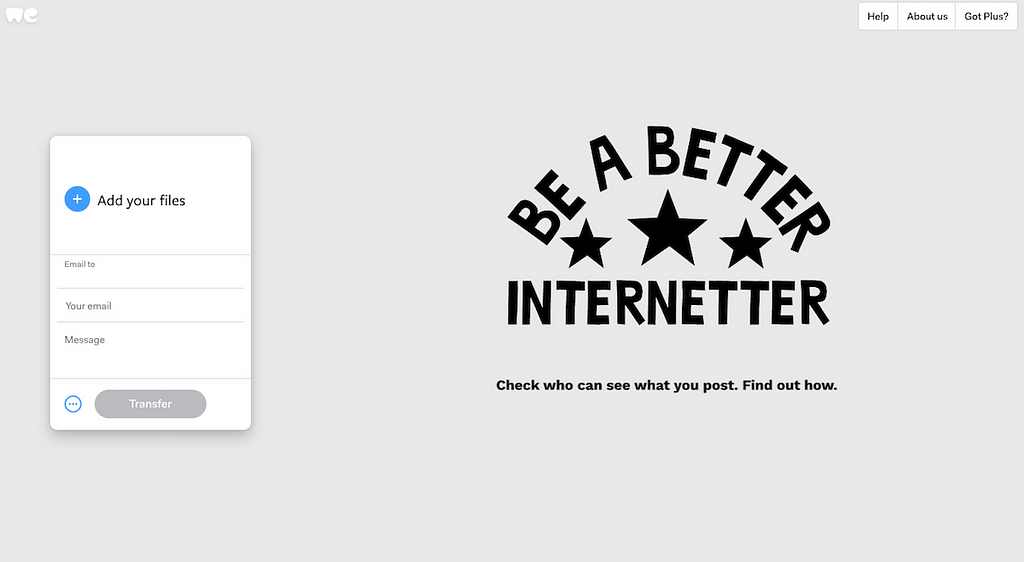

Following the initial launch on the Guardian, we quickly won support from Unruly Media, who ran the adverts across their spaces wherever possible, and WeTransfer supported the campaign with 25m impressions on their wallpaper adverts.

“I’m always amazed that values we take for granted offline are treated so recklessly in the online space. At WeTransfer we’ve always respected the people who use our tools, and so it’s empowering to come across other organisations that are fighting for a better, fairer internet for everyone. We’re proud to stand with Doteveryone and delighted to use our platform to help spread their message to 40 million creative minds around the world.” Damian Bradfield, President of WeTransfer

And there’s recognition in many different quarters of the need to help the public navigate the impacts of technology on their lives.

Last week’s Commons’ Culture, Media and Sport Committee report into fake news called for a ‘unified public awareness initiative’ funded through an educational levy on social media companies to help people understand how social media functions and how their data is used.

The Royal Society of Public Health is launching ‘Scroll-free September’ to help people find a more balanced relationship with social media.

And the startup body Coadec has included public confidence in technology based on digital understanding as one of its proposed principles for the government’s digital charter.

After the summer, we’ll be publishing detailed recommendations on the infrastructure we think is needed to support digital public health as part of our Regulating for Responsible Technology research.

2. People liked the adverts but we don’t know yet how much they helped.

As well as support for the campaign overall, we got feedback that people really liked the individual adverts and the light-hearted, positive approach.

Alongside the campaign we compiled lists of tips for people to put into practice and asked others to share theirs.

Clicking on the adverts took people to information about how to use private browsing, change to a chronological social media feed or check their privacy settings.

People clicked through most to the information on social media feeds and how to turn on chronological timelines in order to get access to a range of different news and information, as opposed to posts based on what you, and the people you’re connected to, have clicked or commented on in the past.

But we don’t yet know why. Was it because that ad was more attractive? Was it because that’s the thing people feel most strongly about? Or was it the thing that was most new and interesting to them?

We’re also not able to tell at the moment if people actually acted on the information that they read. We’re planning to do more work to evaluate all that.

It also became clear there’s a real lack of consistent, independent and clearly worded information to help people take simple steps to make their tech work better for them. We think this is a gap that needs urgent attention.

3. We were probably trying to do too much in one go

We wanted to use the campaign to address some of the public’s five digital blindspots identified in our People, Power and Technology research on the nation’s digital understanding — targeted advertising, data collection, business models, filter bubbles and dynamic pricing.

In the end, we only focused on three of them, but that still meant we were covering a lot of ground with one campaign. That and we were trying to both raise public awareness and drive behaviour change in the space of just a few words and images.

In future we want to identify one specific issue and behaviour to focus on and really drill down on who the best audience for that. We’re grateful to the friendly critics who helped us see that — we always welcome feedback, not just praise!

4. It’s a fine line between empowering the public and blaming them

We want to galvanise the public to demand more responsible technology. But there’s a danger of pushing the burden back onto users.

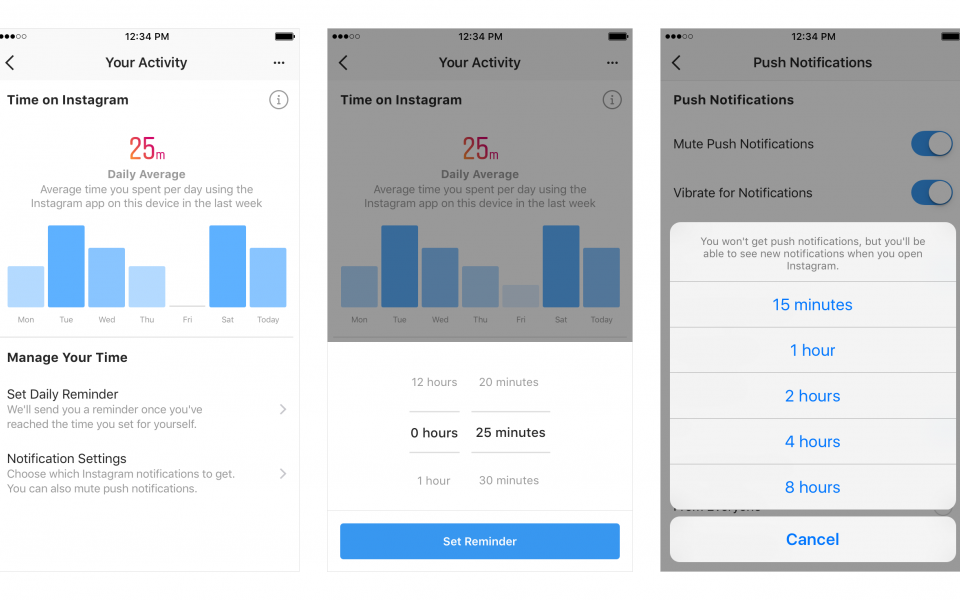

This week Instagram and Facebook announced tools which allow people to monitor and set limits on how much they use the platforms. Apple and Google have already created similar functions.

In some respects, that’s a positive step towards empowering the public. But if the underlying design of the platform is addictive, it’s giving the public responsibility for a problem created by the platform, while doing nothing to address the root cause of that problem.

Digital understanding is essential, but we mustn’t make it the solution to all of technology’s problems. We don’t want our campaign to absolve industry of its obligation to create responsible technology or to distract from government’s responsibility to hold technology to account.

So what’s next?

We’ve loved doing this work — we’ve learned so much and it’s great to have won so much support so quickly.

We hope to continue to work with partners to evaluate and refine the campaign, explore how movement building techniques can help address these issues and activate the goodwill we’ve uncovered to ensure there’s a coalition of people and organisations who can sustain this kind of work in the long term.

If you’d like to be involved, let us know [email protected]

Some lessons from building a digital public health campaign was originally published in Doteveryone on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.