The Office for Responsible Technology: Supporting people to seek redress

Earlier in October we published Regulating for Responsible Technology: Capacity, evidence and redress. In the first in a series of four posts, I roughly sketched out the report’s proposal for a new independent regulatory body — the Office for Responsible Technology — to empower regulators, inform the public and policymakers around digital technologies and support people to seek redress from technology-driven harms.

This post describes in greater depth the last of these three functions and explores how the Office can raise standards for complaints handling across the tech sector and enable the public to hold the public and private sector to account for the negative impacts of their digital services.

In July this year a paper by UCLA academic Kristen Eichensehr, explored the evolving social contracts between technology companies, nation states and their users. In the internet’s formative years, users sovereignty reigned supreme and the web remained largely beyond the control of government. As it scaled exponentially, the state began to assert their authority over the online world, with digital companies as willing allies.

Today, multinational tech giants’ influence exceeds, and in some cases challenges, that of world’s nations states. Against this backdrop such companies have begun to acknowledge that with this great power comes great responsibility.

“We therefore should commit ourselves to collective action that will make the internet a safer place, affirming a role as a neutral Digital Switzerland that assists customers everywhere and retains the world’s trust” Microsoft’s Brad Smith, February 2017

But the regulatory system has yet to fully adapt to this redistribution of civic duties. Some regulators still tend towards a punitive “command-and-control” approach to regulation, leaving less room for companies to innovate to protect users and ensure society can hold them accountable for their measures.

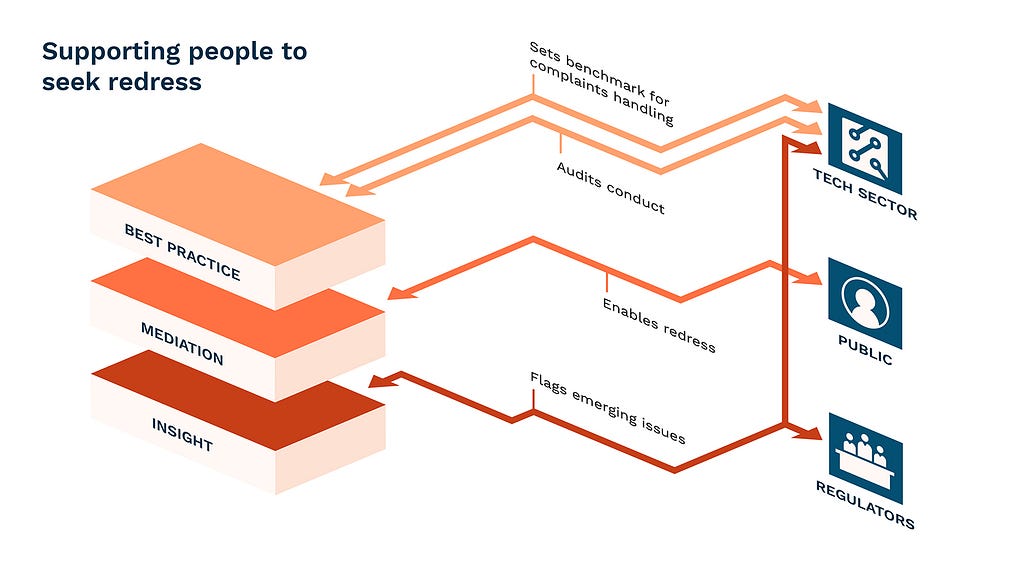

The Office for Responsibility would champion a new model of accountability and redress by:

- Dealing fairly with public concerns by setting and auditing best practice standards in the managing digital disputes

- Enabling backstop mediation where these standards aren’t being met through alternative dispute resolution and investigation. These functions may be devolved to the existing/ future ombudsmen associated with particular sectors, or kept as an independent function within the Office.

- Sharing insights within the system. Through working on the front line of digital harms, the Office is able to flag issues at an early stage and advocate for the public online.

1. Dealing fairly with public concerns

“We absolutely see ourselves having a broader set of responsibilities…We need a principles-based approach that starts with the harm you are trying to tackle that leaves room for innovation because there is a huge amount of innovation in tackling those harms.” Facebook’s Karim Palant, addressing the Science and Technology Select Committee

The sheer scale of digital harms (recent Ofcom/ICO research estimates 45% of adults in the UK have directly experienced some form of online harm) means an oversight body can’t deal with this volume of complaints alone. Tech services must shoulder the majority of the burden in the first instance. And recent comments along the lines of the above from global tech leaders show the sector accepts, and wants, this responsibility for addressing the harms associated with their services.

If we are to entrust digital platforms with developing measures to protect us online however, society has a right to ensure their solutions work.

The Office for Responsible Technology is needed to give the public confidence in their use by:

- Auditing technical and commercial processes for handling user complaints. (e.g. by verifying the effectiveness of AI tools to identify offensive memes or spot-checking complaints hotlines)

- Benchmarking and reporting of complaints handling data (including taking ownership of the Social Media Transparency reporting proposed in the Government’s Internet Safety Strategy). Where owners of digital technologies consistently fail to protect against harms warning notices and fines may be appropriate

- Promoting good practice in mitigating digital harms. Where companies are innovating in emerging areas (e.g. Microsoft’s toolkit to detect Bias in algorithms), the Office can convene working groups of relevant industry groups, regulators and ombudsmen to collaborate.

Theses interactions between the Office and the tech sector must be founded on transparency, independence and evidence. This relationship will be collaborative not confrontational. The fundamental aim will be to drive up industry standards by flagging where protections are inadequate and sharing learnings across the sector. In this way the Office will promote innovation in the public’s interests whilst ensuring that companies are accountable for the solutions they create.

2. Providing backstop mediation

Even with improved standards for handling disputes between tech services and their users, there will inevitably be cases where one of these parties isn’t satisfied, or digital harms slip through organisations’ own safeguards — as Twitter’s public apology for ruling that a threatening tweet by Cesar Sayoc (who was charged in the mailing of explosive devices to over a dozen high-profile political figures in the US last week) not violating its rules shows.

Where digital disputes aren’t resolved through technology companies’ own channels, the Office for Responsible Technology will step in to protect individuals and society.

Exactly how this is done will depend on the nature of the harm and the associated existing regulatory landscape.

We recommend the following sequence for resolving this:

- Prioritising which digital harms require action. The Internet Safety Strategy lists 14 and there are many more outside of its scope. Prioritisation should be done by comparing evidence around their severity (and the Office can play a key role in establishing, as I discuss here) against current or imminent protections and regulation.

- Comparing the options for providing mediation against harms. Where possible existing arrangements should be adapted to tackle digital issues (i.e. the Financial Services Ombudsman taking on new powers to mediate in instances where mortgage lending algorithms have discriminated). New statutory ombudsman could then be established for instances where regulatory capacities is currently lacking (e.g. harmful, but not illegal speech on social media).

- Encouraging organisations to engage with the scheme with both carrots and sticks. For legal compliance from multinational companies different avenues to consider exploring including establishing international enforcement agreements, or assigning a legal representative for the parent company where they have a presence in the UK (learning from EU nations’ similar attempts to enforce the GDPR extraterritorially). Alongside these more legal routes, Ombudsman bodies would also need to use softer approaches (e.g. awarding trust marks, issuing public warning notices naming and shaming organisations that refuse to comply).

For the mediation process itself, the tools currently used by existing ombudsman (e.g. complaints hotlines, dispute investigation and alternative dispute resolution) can be easily adapted to the digital space.

Some digital issues are magnified on a societal level, such as examples like the widespread use of inaccurate facial recognition tech or targeted job ads discriminating against older people.

In these instances the Office would support users to take collective action.

Any remedies (financial or otherwise) offered to individuals should be open to others affected by the same issue. This should help to hold the owners of digital technologies to account for the social externalities of their work.

3. Sharing insights within the system

A collaboration agreement between Ofgem, Citizens Advice and Ombudsman Services in the energy sector is showing early promise. It shows how the insights of ombudsmen can benefit the wider regulatory system. Through working near the front-line of digital harms, the Office will be well placed to flag spikes in complaints at an early stage and encourage regulators, government and technology to act before their problems escalate.

Initiatives such as the European Network of Ombudsmen are an exemplar of a soft-touch way to share approaches to protecting consumers and work towards mutual goals internationally. As new models and bodies for protecting against digital harms begin to emerge in other regions (such as the Australian eSafety Commissioner, who mediate between social media companies and child users in the areas of cyberbullying and revenge-porn), the Office can play a key role in fostering global collaboration.

And collaborations could go beyond simply sharing good practice, they could promote mutual enforcement and information sharing agreements between national ombudsmen operating in similar areas.

Resolving digital disputes and enabling collective redress is not easy. Many of the ideas I outline above are unproven in the UK. But a lack of precedent also represents an opportunity for the UK to lead the way in digital mediation and redress. Alongside organisations such as Which?, Resolver and Citizens Advice, at Doteveryone we plan to how to make this system a reality over the coming months. In time, we intend to be able to hand the baton over to the Office for Responsibility to take this work forward.

Sounds like a good idea to you? Get in touch to discuss how we can make this a reality together at [email protected]

The Office for Responsible Technology: Supporting people to seek redress was originally published in Doteveryone on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.