Start with values: How innovation can be bold, fast and responsible

Wondering how to get from tech ethics to responsible delivery? Understanding your values is the first step to better business planning and more responsible metrics.

Facebook and Cambridge Analytica may have dominated the headlines in 2018 but they shared the “techlash” with lots of other companies. And not all the stories that made the news were about data and privacy. While new ethical codes for AI and ML were being published almost every week, Amazon’s treatment of its warehouse workers, the Google Walkout over sexual harassment policies, Apple’s “Batterygate”, and general political discontent about tech monopolies and tax avoidance showed it’s not just what gets made that matters; how it’s made matters too.

In our research for TechTransformed, Doteveryone’s method for responsible innovation, we learnt that one of the hurdles for improving the social impact of tech is that none of us ever think we’re that person or that company. To some extent, we all mean well and — as there aren’t many cultural norms for sharing our ethical perspectives on life — we tend to assume the products and services we’re creating mean well too.

And, unfortunately, that is often where the trouble starts.

After all, few products and services explicitly set out to grapple with what most non-ethicists think of as ethical questions. Fast, large-scale disruption isn’t looked at through the same critical lens as big ticket dilemmas like deploying Lethal Autonomous Weapons or providing access to justice. And most techniques for building and specifying technology are inherently inward-looking; for instance, QA tends to happen against a product’s own spec, a set of user needs or jobs to be done, not with a conscious view of potential wider impact or consequences.

And so at first glance, the potential ethical and social effects of many digital products and services seem fairly anodyne:

“We want to make it easier for people to share things with their friends!”

“We want to make it possible to get pizza to your door in 15 minutes!”

“We want a world where we can find everyone’s location and offer them useful recommendations because everyone hates choosing where to go out on a Friday night!”

In reality, Facebook, UberEats and GoogleNow are all complex products and services that do a lot more than they appear to say on the tin. But because they all somehow feel familiar and relatable to analogue equivalents — they’re communication channels or delivery services or maps or listings — it’s easy to assume their impact will be the same.

It’s not just data that makes them different; it’s also the business model that sits behind them, the metrics they’re measured against, and the values they are bringing to life.

Fixing responsibility bugs

We’ve identified three interventions in the product process that make it easier to deliver responsible technology without slowing down delivery. Few businesses are equipped to make philosophical deliberation a part of their process, so TechTransformed offers a set of pragmatic improvements that make it easier to reconcile big-picture ethics with hands-on delivery.

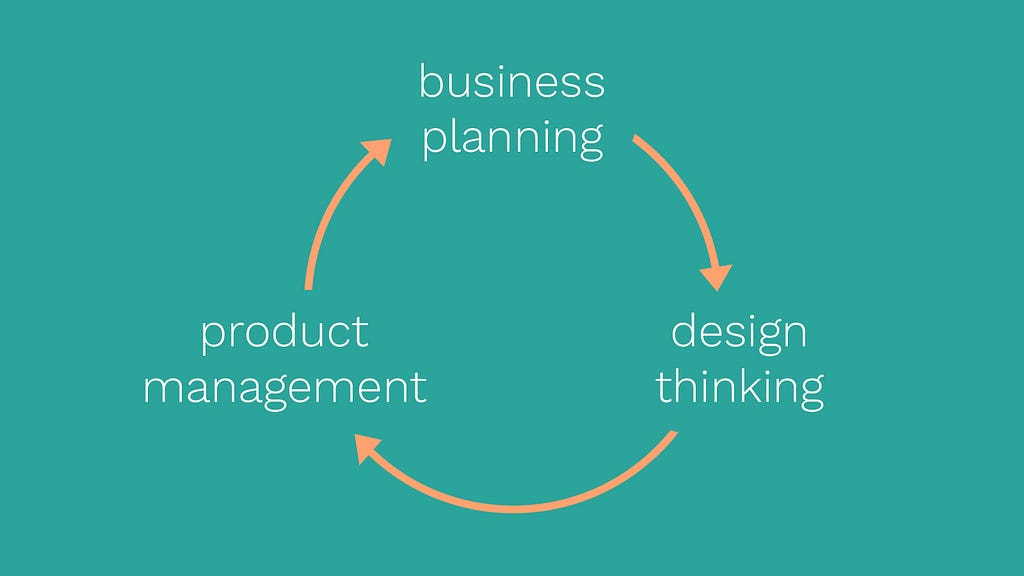

Small changes to business planning, design thinking, and product management can help boards and teams to make conscious, deliberate choices about the impact and responsibility of their technology, be more mindful of the compromises their making, and make open decisions about what it’s important to offset or mitigate.

And the first step to doing that is to recognise and understand your values.

Start with values

Ethics is a small word that relates to a lot of big concepts. Many of the ethical codes for software development and AI can be interpreted subjectively and bent to meet a point on most people’s moral compass. For instance, no one would disagree with with an intent to “Be socially beneficial” (Google), “honest and realistic” (IEEE), or “honest and moral” (The Programmer’s Oath). These are very laudable ethical aims that are extremely difficult to map out and deliver: how do you know you have been honest and moral? How do you know when and how your technology has sufficiently benefited society? What are the metrics you’re assessing that against, and how are you reporting it to your board?

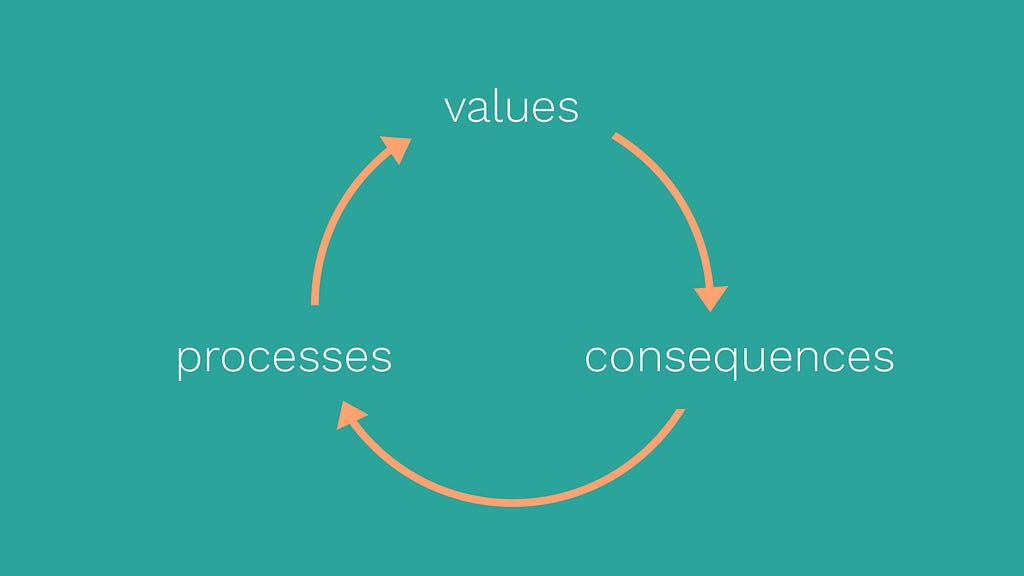

Values mapping helps to break down your organisation’s, your team’s and your personal ethical intent. It allows more specificity so you can add an ethical dimension to your objectives and KPIs. And because what companies, boards and product teams value is also what they measure, mapping your values means you can more easily build ethical considerations into what gets made and prioritised.

So rather than starting with lofty ethical statements, with user needs, or with jobs to be done, starting with values can give your business plan or product strategy a clear and shared direction that will make difficult decisions easier as you go into development.

As management specialist Roger Martin says:

“The very essence of strategy is explicit, purposeful choice … You only know that you’ve made a real strategic choice if you can say the opposite of what that choice is, and it’s not stupid.” (via Russell Davies)

Just as Martin says, “Don’t mistake non-choices for strategy”, the same can be said of values. Most of the things that are good for everyone are in the UN Sustainable Development Goals; nearly everything else creates winners and losers. So if you’re not making something that can objectively be said to be good for everyone, it’s important to start by understanding who you want it to be good for, and who might be missing out.

Sharing your values

Sharing values with others can be difficult. It can involve honesty, soul searching and conflict which might seem like painful and hard work, but it’s the good kind of pain, like ripping off a plaster quickly or going for a run; it often hurts more to anticipate it than to actually get it done.

It’s often easier to assume that your colleagues or your managers share the same values as you — that everyone’s fundamentally a good person and that you all share the same definition of “good” — so we mostly don’t have these conversations. But if you’re creating new technology that might be used in ways you can’t predict or have consequences you haven’t foreseen, you need a clear articulation of your values that you can fall back on when things you hadn’t expected start to happen. I’ve set out four useful questions below that can help to start that process.

Four useful questions

The following questions are a starting point for mapping values. This can be done for an organisation, a product, a team or an individual.

Bear in mind that …

- As an individual, there might be a mismatch or a compromise between your personal values and the place you work in or the project you’re working on. After all, most people can’t choose their work based on their moral interests. If that is the case, and you have the time to do it, it’s still useful to express the compromise and understand more about the lines you will and will not cross.

- Your answers to these questions will change over time. Both as an individual and as a business, your financial and social comfort will influence your answers as much your instinctive moral response.

- There might be a mismatch between your practical, today answer and your aspirational, long-term answer.

- When you examine the business decisions you make, you might find they don’t reflect your personal moral compass or comfort. If that is the case, it’s up to you to decide whether you’re comfortable with the possible consequences of your business choices, and whether it’s appropriate to change or mitigate them.

These questions aren’t meant to solve those problems, but they’re a starting point for decision-making and objective setting that will move your organisational, team or product behaviour closer to the values you want to uphold.

1. Who do you value most?

- As a board or a leadership team the first challenge is to answer this question: who is most important to you — is it your shareholders, investors or stakeholders, your workforce, your customers or your clients?

- If it’s your customers or clients, then be specific about which segment: is it the most vulnerable, the most engaged or the most profitable?

- When you need to compromise, who do you feel comfortable benefitting, and who do you feel comfortable disadvantaging?

2. What do you value most?

- Start internally, and pragmatically. This might be your craft, your ability to innovate, your colleagues and collaborators, the investment, or the opportunity you have.

- And externally, what do you work the hardest maintain? This might be trust, sustainability, reliability, or security. Or it might be reputation, profit margin, or pipeline.

3. What value do you create?

- And who is it that value for?

4. What behaviours do you value?

- What are the adjectives that describe the ways you or your team achieve things when you’re at your best?

- What do you look for and champion in others?

Having clear answers to these simple questions will help you to set better metrics and help turn what might feel like intangible factors into shareable successes, meaningful quality assurance, and ongoing performance management.

We’ve made TechTransformed because we want to make it easy to make technology better. Embedding what you value in your business planning will help you stay close to what’s important as you make new things happen. Innovation doesn’t have to be about moving fast and breaking things; it can also be about achieving what you believe in.

TechTransformed is a set of methods and resources that innovators can use to put responsibility at the heart of their business planning, design thinking, and product management. Our tools and methods help boards and product teams map their values, design for consequences, and adopt responsible processes.

Sign up for more information and to be a beta tester>

Start with values: How innovation can be bold, fast and responsible was originally published in Doteveryone on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.