Can women dream of different futures? Using science fiction to make new myths and maps for technology

Science fiction as a way of making new futures is a popular topic right now. We’re doing some work at Doteveryone to see if different kinds of science fiction can encourage a better gender balance in the technology industry. This post explains why.

In 2017, the technology industry feels pretty heroic. And I use that word advisedly.

Mark Zuckerberg probably doesn’t need to run for president because he’s already running Facebook; Elon Musk’s ambition is quite literally out of this world; Jeff Bezos has a hand in every aspect of human existence from baby wipes to banking; Tim Cooke has taken spiritual advice from the Pope; Eric Schmidt is getting machines to learn faster than humans.

And the scale of ambition is mythical and jaw-dropping. The rate of progress unstoppable.

But in spite of this hunger to make the future, the technology industry has some pretty old-fashioned ideas about women.

The firestorm at Uber is just the latest in a never-ending stream of stories about terrible workplace culture and unimpressive statistics. Only 1 in 10 decision-makers at VCs are women, there are 0 women running the 5 most valuable technology companies in the world, only 9% of executive officers in Silicon Valley are women, only 12% of engineers are women. The 12 best tech companies to work at “as a woman” are all run by men. It goes on and on and on.

This either means that getting to a representative gender balance, closing the gender pay gap, and creating a considerate workplace culture is more difficult than getting into space, organising the world’s information, or enabling 1 billion rides in 57 global cities.

Or it means we’re doing it wrong.

On the face of it, that’s puzzling. There’s no shortage of gender diversity programmes. There’s training to combat unconscious bias, anonymised recruitment processes, support groups, confidence training, gender diversity ambassadors — there’s even a day to celebrate women in tech. And while all of these things make some change, it’s not dramatic, fast or profound.

That might be because it’s not the right kind of change. It’s applying a sticking plaster to a broken wrist, not resetting the bone.

Rather than simply encouraging women to operate more effectively in a man’s world, and asking men to accommodate them, we also need to let women’s worlds emerge. For the industry to really change, new universal stories and shared references points are vital because a gender-balanced industry can’t exist without gender-balanced inputs and outputs.

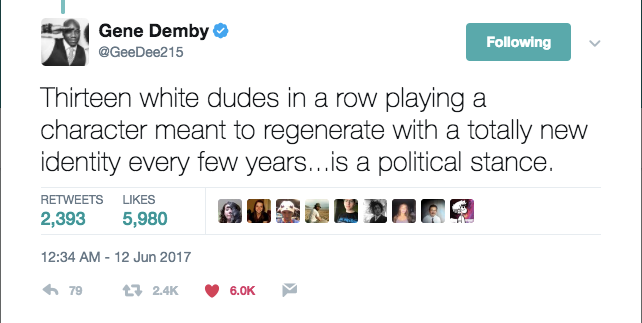

Or, in other words, it’s about time we had a black, female Doctor Who.

Science fiction has long been the mother of invention. Jules Verne’s novels inspired the helicopter and the submarine, and Star Trek’s been beaming new ideas to budding inventors 50 years, from the mobile phone to QuickTime to Amazon Alexa. These initial fictional objects were all imagined to be used 20,000 leagues under the sea or when stuck in deep space. They’re from stories of brave adventurers, far from home. And the inventors they resonated with were mostly men: people who saw a possible future being projected and took permission to act.

Of the current crop of technology heroes, Elon Musk stands out. He’s both a maker of myths and a reader of stories. He’s daring, adventurous and godlike, and projects his (omni)potence through his grand, phallic schemes. He works to different standards and flies near to the sun. If you’re keen on a metaphor, it’s not a reach to say he’s f*cking the world, with his long-lasting batteries, boring machines pushing through to the earth’s core, and rockets launching into the sky.

When poor working conditions in one of the Tesla factories were revealed, he took a super-human view of the inhuman things he was asking of others: “I knew people were having a hard time, working long hours, and on hard jobs,” he said. But rather than solving the problem by, say, adding more people or changing the production targets he offered a strange kind of empathy: “I wanted to work harder than they did, to put even more hours in.” (my emphasis)

Musk is welcomed into industry myth so easily because his products embody the excitement that lots of Internet people feel about making real things — the jouissance of ejaculating bytes into bits that makes people excited about things like the Citymapper bus.

This scale of ambition doesn’t come from researching user needs (although, for what it’s worth, my 4 year-old said today, “Whenever I see a picture of space, I want to go there”, so maybe I’m wrong). It’s a much more essential drive. He is famously a fan of the Iain M. Banks Culture novels, and he’s fearlessly pursued impossible possibilities. Neuralink — his brain/robot interface — brings to life the “neural lace” of Banks’ novels; Musk is rising up to the challenge of the imaginative world, and recreating it on earth.

Seeing your values and ambitions reflected in a fictional world — the feeling, say, of reading “Catcher in the Rye” when you’re 13 and thinking J.D. Salinger wrote it just for you — connects us back to the rest of humanity. Or, as @megsauce said on Twitter:

Women’s science fictions don’t take hold in society in the same way as men’s. Frankenstein is, I think, the notable exception, but it’s retelling rarely focuses on the one thing the story intentionally lacks: a mother. More optimistically, it may have taken 32 years for The Handmaid’s Tale to be adapted in a TV show, but it’s finally happened. And the loop is closing: Naomi Alderman is already working on the adaptation of her terrific novel 2016 The Power. (Laurie Penny talks about this more although she doesn’t address the ongoing mystery of why men don’t read many books written by women; perhaps because they worry they’ll be “all about love”.)

But to return to Elon Musk, where are the women who share his other-worldly scale of vision? What stories do they need to spark their imaginations? What shared cultural references can give them the confidence to even share their dreams, let alone have the hunger to make it a reality?

Shared cultural references and artefacts are a cornerstone of having legitimacy and permission to act — permission from yourself, and from others. They let others take short-cuts to understand who you are and what you’re trying to do, and connect you back to confident utopia of an imaginary world. People don’t have to be so scared of you if they’ve seen the change you’re trying to make happen on TV. This is going to be difficult to measure, but I’m willing to bet a black, woman Dr Who would do more for unconscious bias among Dr Who-watching men than any amount of diversity or consciousness-raising workshops.

Of course, this kind of cultural manipulation may take years to yield return, and it’s certainly not a magic bullet. But I want to open a different kind of conversation about gender equality in tech: one that doesn’t make it women’s fault for not leaning in, one that gives men confidence to let women take a role, one that shows futures that different people feel inspired and encouraged to rise to the challenge of making. If we support this long-term change with short-term fixes that delegitimise outright sexism (better hiring, workplace codes of conduct, paying men and women the same) then we can make a more gender-balanced industry together.

I say this all as a woman who’s worked in tech since the 1990s, at a time when having an English degree and no real experience made you no better or worse than anyone else. I have a theory that I kept going — despite being chased round the office by more senior men, having to negotiate a 3-foot-no-touching rule with certain male colleagues, and much more besides — because I’m good at it, and because my dad is an engineer, so there was an ease and familiarity to the way people spoke about things and turning abstract problems into reality.

But even though I’d inherited some legitimacy, it took me a long while not to feel like a charlatan, because in the early days of the Web I was one of the few people I knew who didn’t own a games console and gave zero shits about Mad Max. I didn’t quite fit, I didn’t get jokes, I still have no idea what the big deal is about Towels.

And while I’ve been able to opt-out of male-dominated workplaces for the last few years, I still get to use the products that a male-dominated industry makes: fitness trackers that don’t track menstruation or count steps when you’re pushing a buggy, phones I can’t reach my hands around, productivity apps that assume regular working patterns. And while I also order take-aways and stream video, they’re not the problems I needed to solve first.

So while we do all the more obvious things about making the industry better, let’s do some non-obvious things too. We’re going to do some experiments at Doteveryone over the rest of this year around making different futures. There’s already a flourishing alt sci-fi scene, but for whatever reasons, those stories remain “alt” — how can we make them mainstream?

The changes we’re looking to make are attitudinal:

- what kind of stories will inspire a generation of girls? Is there an equivalent to Marty McFly’s hoverboard or the holodeck on the Starship Enterprise?

- what kind of cultural artefacts do we need to give different kinds of legitimacy in an industry dominated by young men?

- what kind of stories will this generation of nerdy dads want to share with their daughters?

- what kind of dreams and futures can we seed in the minds of investors, makers and inventors, so they broaden their horizons?

We’re starting with a small research project (led by Yasmin Khan and Annette Mees), but we’re also looking for partners and funders to make the change we really want to see, whether that’s on billboards or bookshelves, but mostly in people’s imaginations.

Making technology fairer is not simply something that happens in design patterns; it needs systemic change. Some things will be small and obvious, others abstract and brave. The opportunity we have as technologists is to continue to change the world completely; let’s do it in ways that represent as many people as possible.