Executive Summary

The public is once again recalibrating its relationship with technology. The pandemic lockdown has accelerated even further the already dizzying speed of technological change: suddenly the office has become Zoom, the classroom Google and the theatre YouTube.

The transformations wrought in this period will be lasting. The outcome of this period of increased tech dependence must be one where technology serves people, communities and lanet.

Doteveryone fights for better tech, for everyone. To achieve this it’s vital to listen to – and respect – the views of the public. This report puts the people who are experiencing this tremendous transformation front and centre.

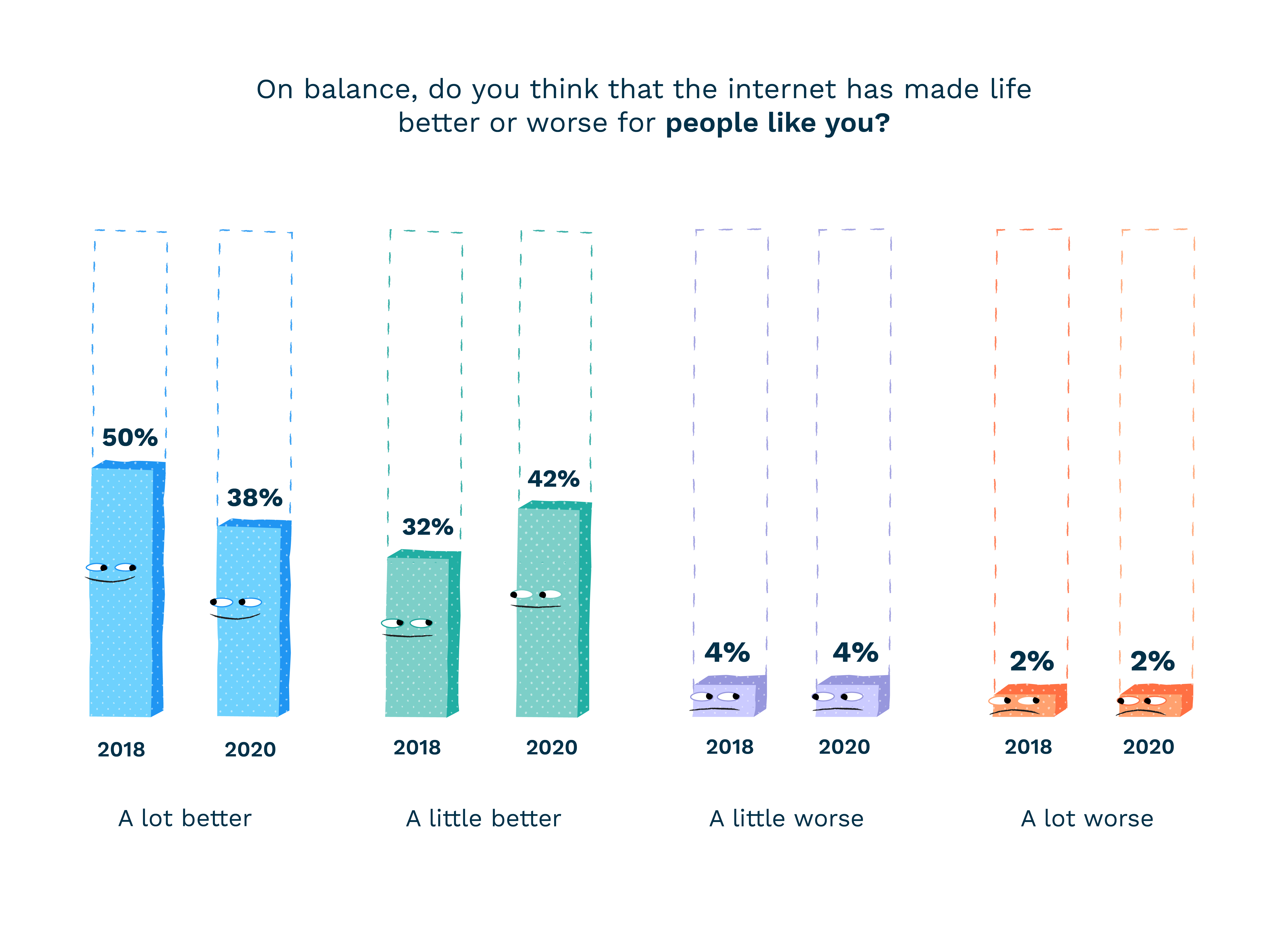

Based on our groundbreaking 2018 research, we ran a nationally representative survey just before lockdown and focus groups shortly after it began, benchmarking the public’s appetite, understanding and tolerance towards the impacts of tech on their lives.

This year’s research finds people continue to feel the internet is better for them as individuals than for society as a whole. But the benefits are not evenly shared: the rich are more positive about tech than the poor, risking the creation of a new class of the ‘tech left-behind’. And it finds most people think the industry is under-regulated. They look to government and independent regulators to shape the impacts of technology on people and society.

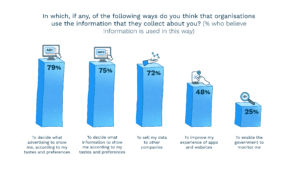

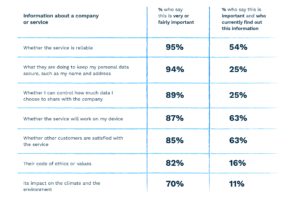

It finds that although people’s digital understanding has grown, that’s not helping them to shape their online experiences in line with their own wishes. They still struggle to get information about the issues that matter and to choose services that match their preferences.

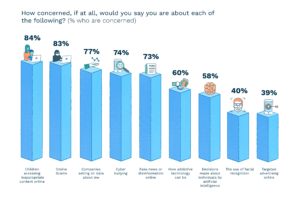

And it finds people often don’t know where to turn when things go wrong. Even if they do report problems, they often don’t get any answers. They mistrust tech companies’ motives, feel powerless to influence what they do, and are resigned to services where harmful experiences are perceived to be part of the everyday.

The current societal shift is an opportunity to shape a fairer future where technology works for more people, more of the time. Our practical recommendations to government and industry provide clear steps to make that happen.

Key findings

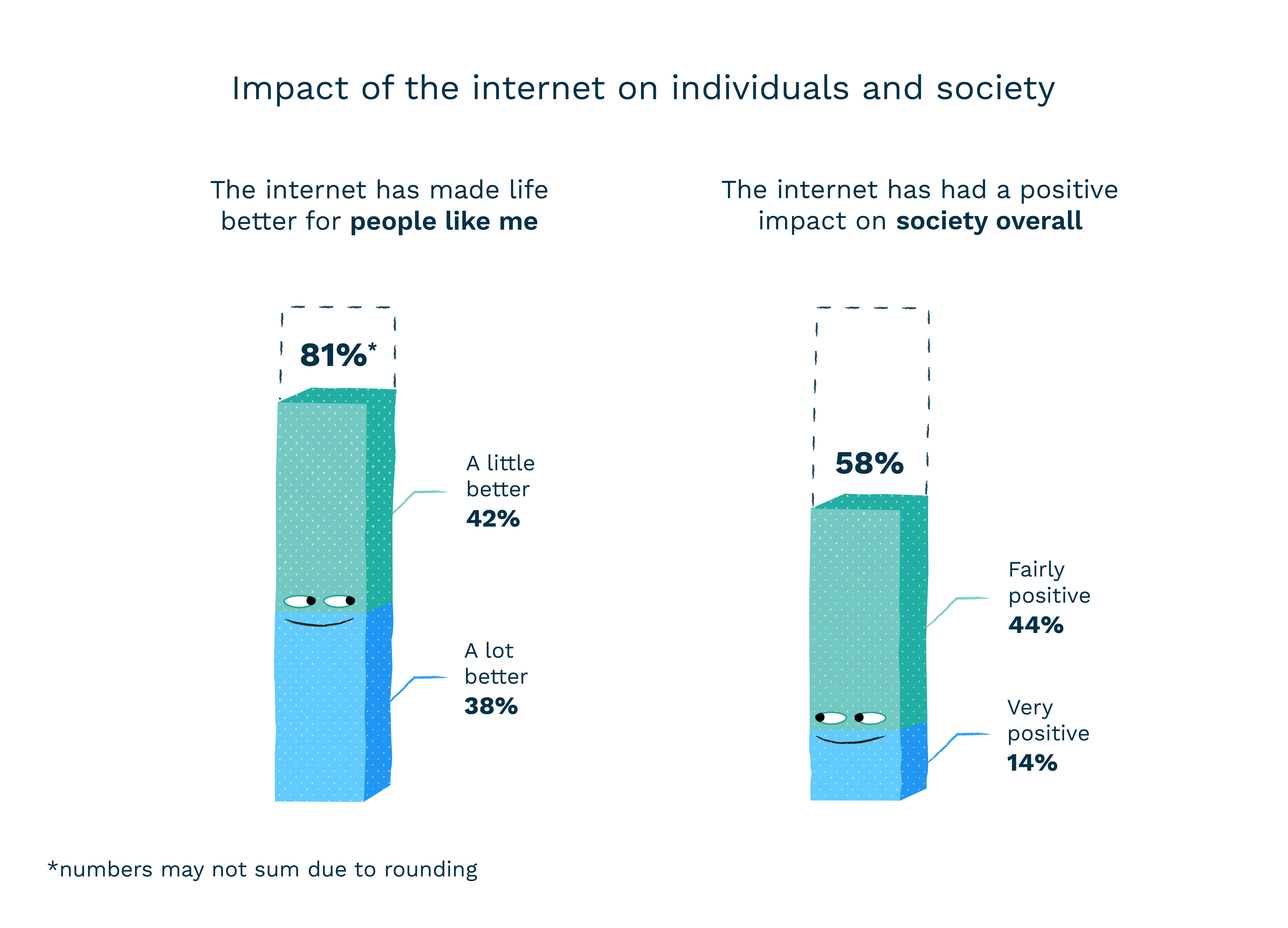

The vast majority of people think the internet has improved their lives but are less convinced it’s been good for society as a whole. 81% say the internet has made life a lot or a little better for ‘people like me’ while 58% say it has had a very positive or fairly positive impact on society overall. Only half feel optimistic about how technology will affect their lives (53%) and society (50%) in the future.

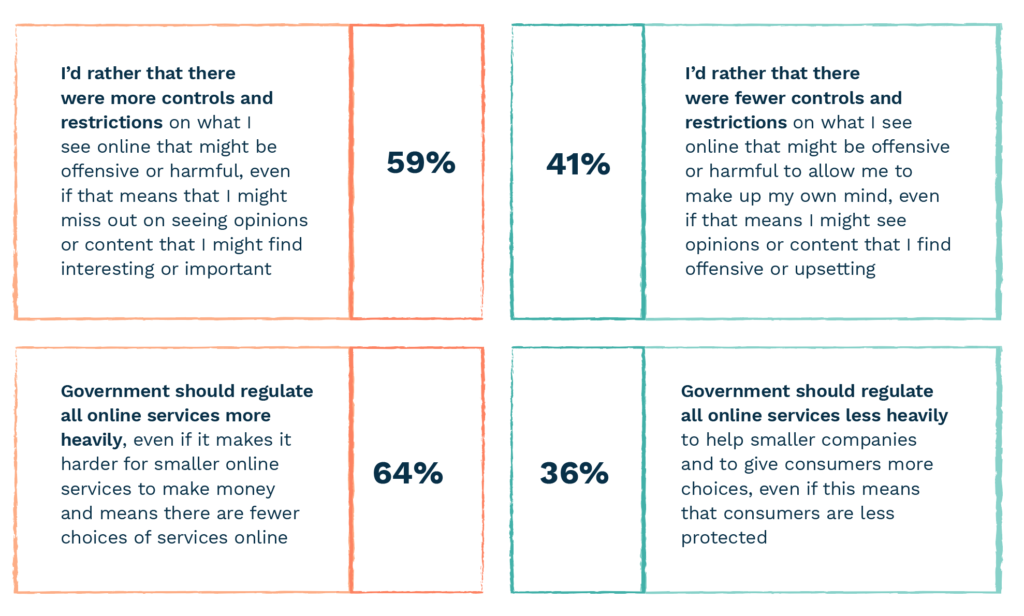

58% of the public say that the tech sector is regulated too little. They identify government (53%) and independent regulators (48%) as having most responsibility for directing the impacts of technology on people and society.

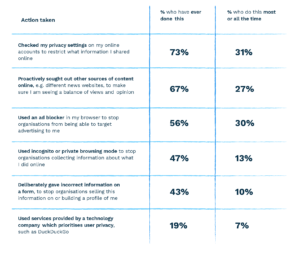

People are taking a range of measures online that stem from their digital understanding. Most people have checked their privacy settings (73%), looked for news outside their filter bubble (67%) or used an ad blocker (56%) but people tend to take these actions only occasionally.

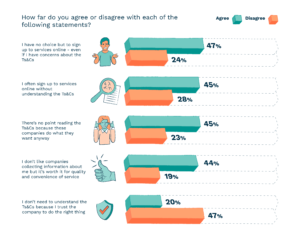

Nearly half (47%) feel they have no choice but to sign up to services despite concerns and 45% feel there’s no point reading terms and conditions because companies will do what they want anyway.

Over a quarter of the public (26%) say they’ve reported experiencing a problem online but that nothing happened as a result. More than half would like more places to seek help (55%) and a more straightforward procedure for reporting tech companies (53%).

Only 19% believe tech companies are designing their products and services with their best interests in mind. Half (50%) believe it’s ‘part and parcel’ of being online that people will try to cheat or harm them in some way.

Recommendations

We recommend the creation of an independent body, the Office for Responsible Technology, to lead a concerted, coordinated and urgent effort to create a regulatory landscape fit for the digital age and ensure the benefits of technology are evenly shared in a post-pandemic world.

We recommend all tech companies implement trustworthy, transparent design patterns that show how services work and give people meaningful control over how they operate. The Competition and Markets Authority, in coordination with the Information Commissioner’s Office, should set and enforce best practice for understandability, transparency and meaningful choice for the platforms where people spend most of their time online.

We recommend the Government should base its forthcoming media literacy strategy around new models of public empowerment for the digital age that:

- Meet people where they are, with opportunities to act embedded into products and services

- Provide information that’s specific to the issue and tailored to the individual’s capability and mindset

- Enhance rather than detract from current online experiences and create feedback about the impact of any action, creating the motivation to act.

We recommend all tech companies create accessible and straightforward ways for people to report concerns and provide clear information about the actions they take as a result. And we recommend the incoming online harms regulator provide robust oversight of companies’ complaints processes founded on seven principles of better redress in the digital age:

- Design that’s as good as the rest of the service

- Signposting at the point-of-use

- Simple, short, straightforward processes

- Feedback at every step

- Navigating complexity

- Auditability and openness

- Proportionality

We recommend that digitally-capable super complainants should be empowered to demand collective redress from technology-driven harms on the public’s behalf and to channel unresolved disputes between individuals and companies. And we call on the Government to support coordination for civil society organisations helping people to address the impacts of technology-driven harms on their lives.