Imagining Better Care Systems — five ideas for a fairer future

Imagining Better Care Systems — five ideas for a fairer future

Part 2 of 2: ideas for how tech could help us build a better care system from people in the care sector

The first of this two-part series of posts looked into the practicalities of designing a series of inclusive and accessible workshops with people who have personal and varied experiences of the care sector.

We shared some of the things we did, and some of the things we did not anticipate, but would take into account next time.

Here are just five of the ideas we imagined in them, for how tech could help us build a better care system.

Again, it’s important to say that we are enormously grateful to everyone who participated in the workshops, and everyone who couldn’t travel but let us visit their support groups or had an interview over the phone.

These ideas will feed into the rest of our work going forward, including a short film we’re making with Superflux. We look forward to sharing it 🔜.

How tech could help us build a better care system. Five ideas.

1. Could technologies enable more people to care and contribute?

Pretty much everyone wants to be able to contribute to their community, to feel valued and to have purpose.

Being active and involved is great for our mental and physical health, whether we have complex access needs, or multiple chronic health conditions, or are near the end of our life.

People want more than to be kept alive. They want relationships, careers, to learn, to share their skills and ideas and to look after one another. They want to exchange care; the person with fine motor control challenges who can drive the friend with limited sight to the shop, and help one another with shopping.

When they are well-supported people can get a lot of value, purpose, and joy from caring. But this can also leave people open to exploitation.

Work that provides ‘its own reward’ is not less deserving of fiscal reward. Too many people in caring professions or who care for family members are suffering, which makes it difficult or impossible for them to care well.

How could technology support people to work, volunteer and contribute whilst flexing around changing healthcare issues and support needs? How can we support ways to work or volunteer flexibly that don’t threaten people’s income through a hostile benefits system? How can we enable people living together in supportive environments without them becoming ghettoised?

As concrete examples, there was a lot of hope for how telepresence could open up new ways to work and connect from home, and for support services which are accessed via apps which could help people travel alone safely.

2. In the face of automation and datafication, how can we create more space and time to develop relationships of trust?

The best and most effective care relationships include friendship and fun, alongside skill and safeguarding. But these kinds of relationships can’t develop when you’re racing through tasks in a 15-minute care visit, with frequent changes of staff, staff working past the point of exhaustion, or staff ratios of a dozen care home residents to each worker.

“Someone needs to love you before they will really advocate for you when things are hard.”

Workshop participant

This is true beyond the formal care sector. When routine services such as libraries, GP surgeries, or even coffee shops all cut staffing and push high targets, there is no time to build trust, familiarity, and community.

“Good relationships keep us happier and healthier.”

Robert Waldinger, Director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development

There is plenty of evidence that relationships protect our health, and that loneliness is deadly. We had a lot of anecdotal evidence in workshops that when relationships could develop in the care system it saved money. One person decided against visiting hospital because they could get advice from a trusted support worker. One care professional, because they knew their client, noticed early signs of infection and could avoid a hospital visit. And groups of support staff and clients, who knew and trusted one another, had come up with creative solutions to overcoming barriers to exercise and work.

But as a whole society, we are failing to value care because we struggle to measure it. How do you protect things as difficult to measure as emotional bonds, trust, safety, against the relentless pressure to increase ‘efficiency’?

3. How can tech support greater advocacy and the sharing of information?

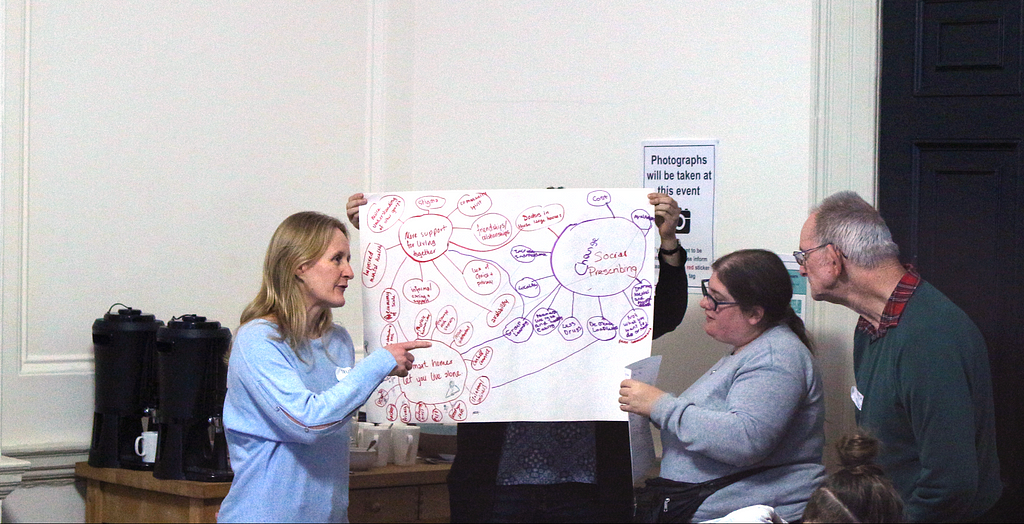

Several times during the workshops people described a problem, only to find that someone on the table could help with a solution. Sometimes this was technological — someone would describe a dream tool, only to hear it already existed. Other times it was legal — how to challenge insufficient wheelchair funding, or finding out about rights to benefits and support.

The benefits and care system feels like an endless maze to many who are part of it. But there is real potential for technology to help with understanding and advocacy. Simple explanations of rights or routine challenges might be helped by apps like DoNotPay which already helps users avoid unfair parking fines and challenge “data breaches, late package deliveries, and unfair bank fees.”

For more complex issues well designed online courses and platforms could support learning and the sharing of advocacy skills in the community.

People involved in the care system also want better ways to find out about the technologies available and to share ideas about how to best use them. They want to know important information like how much they cost, their risks and benefits and how to access them.

They had different ideas for solutions including a single ‘Amazon for care tech’ site, or certification like the NHS Information Standard to encourage the market to provide better quality information and increase trust and in the care products and services they use.

4. Could a Royal College of Carers raise the status of caregivers?

Participants talked a lot about how the low status of caregiving impacted their lives. Several professionals said they had lied about their job to avoid being insulted or belittled. People who cared for family members said they were often assumed to be lazy, or patronisingly told that they were “good” or “sweet” for caring. These comments, they felt, erases their hard work and made their partner or relative’s needs sound like luxuries.

Care professionals, unpaid carers, managers and providers all agreed that low status caused practical difficulties in care. It contributes to the problems in hiring and retention, making it harder to find and access support. It contributes to a media narrative of care recipients as undeserving and carers as low-skilled and thus poorly paid.

While there are formal qualifications available for carers now, such as NVQs up to Level 5, and these and other options are promoted in the Government’s “Every Day Is Different” campaign, people in our workshops described a different reality. They all agreed that training tends to be minimal. One reported getting just one day’s training on starting the job- and then being removed halfway through that day to do their first care visit. Others described waiting years between “annual” reviews. Much of the training that does happen is proprietary to an employer- so if you join a new agency you need to start again on lower pay and do the same training all over again.

People in our workshops hoped that technology could be used to raise the status and skills of the profession. They imagined a Royal College of Carers which would make lessons available freely online. It would support modular long term career pathways with specialisms and be accessible to unpaid family carers to help them better look after family members, or even ease a transition from unpaid carer to a new career. It would include modules that taught advocacy skills and about both carer and care recipient rights, that reward the ability to navigate a complex, locally varied care systems, on-the-job learning, hands-on experience and emotional skills.

5. How can we ensure we develop technology to enable, not replace?

A recurring theme in the workshops was fear and uncertainty. Many people worried that technologies would be used as an excuse to cut services, even if the technology was inappropriate or broken.

But technologies could support better care if development responded to current needs and frustrations.

An enormous amount of caregiver’s time is currently taken up by bureaucracy. Some estimate about 1.5 hours per 8-hour shift. A lot of this information is never digitised, but sits in a paper care plan, only updated and checked on rare occasions. Digitising these systems, and automating some of the collection of data could save an enormous amount of time and create a better evidence base to see the impact of different technologies and policies.

There is already a lot of innovation and investment in software for care providers, and while less glamorous than robot caregivers, these systems offer a lot of hope for improvements and cost savings.

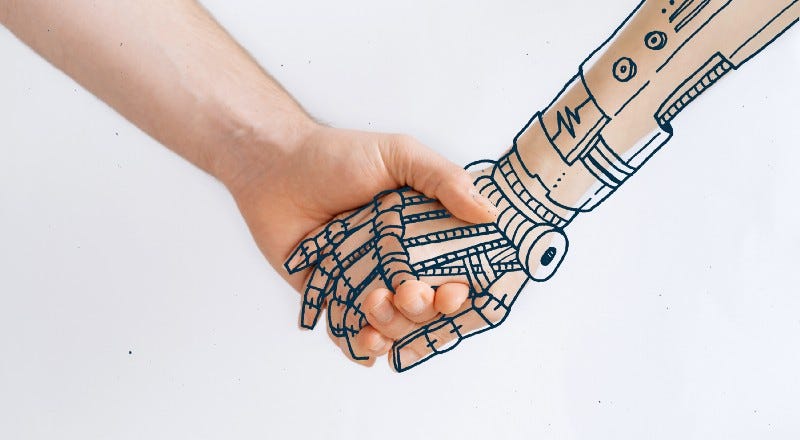

Sometimes the desire for support over replacement is very literal. Quite a few people at the workshops were appalled by the photos we shared of robots lifting people because, to them, it was obvious these lifts would be painful or dangerous and weren’t supporting weakened muscles or painful joints. They were much more interested in pictures of exoskeletons that assist carers — technology which gives extra strength and back support to a highly skilled, empathetic human.

More about the Better Care Systems Project

At Doteveryone, we believe that technology cannot replace care, but used well it could support radical social and structural change, taking us towards a future care system that is sustainable, fair and effective.

Our Better Care Systems project, supported by Google,org, aims to understand the current challenges facing the people who use care services, carers, care professionals, technologists, activists, providers and policymakers (including many people who fall under more than one of these labels), and explore how we can build better and fairer care systems in a future of robots, exoskeletons, and smart homes.

Want to get involved?

Contact us via [email protected].

And to stay informed on the general progress of this work, make sure you sign up for updates. (We won’t use this more than once a month).

Imagining Better Care Systems — five ideas for a fairer future was originally published in Doteveryone on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.